A Royal Lie: King Gustav III and the Slave Trade He Covered Up

In 18th-century correspondence, King Gustav III denied any Swedish role in the slave trade – even as he profited from it.

In my previous article, I wrote about Sweden’s role in the transatlantic slave trade and the country’s enduring reluctance to confront the darker chapters of its past. A colonial amnesia that, until recently, and to some extent still today, shapes the way Sweden sees itself.

But this selective forgetting is far from a new invention. It has deep roots. In Swedish newspapers, travelogues, and books from the era, criticism of slavery was indeed common – yet it was most often directed at others. The horrors of American or French slavery were quite frequently condemned with moral outrage, while reports about what was happening on the Swedish colony of Saint Barthélemy were fewer and far more restrained.

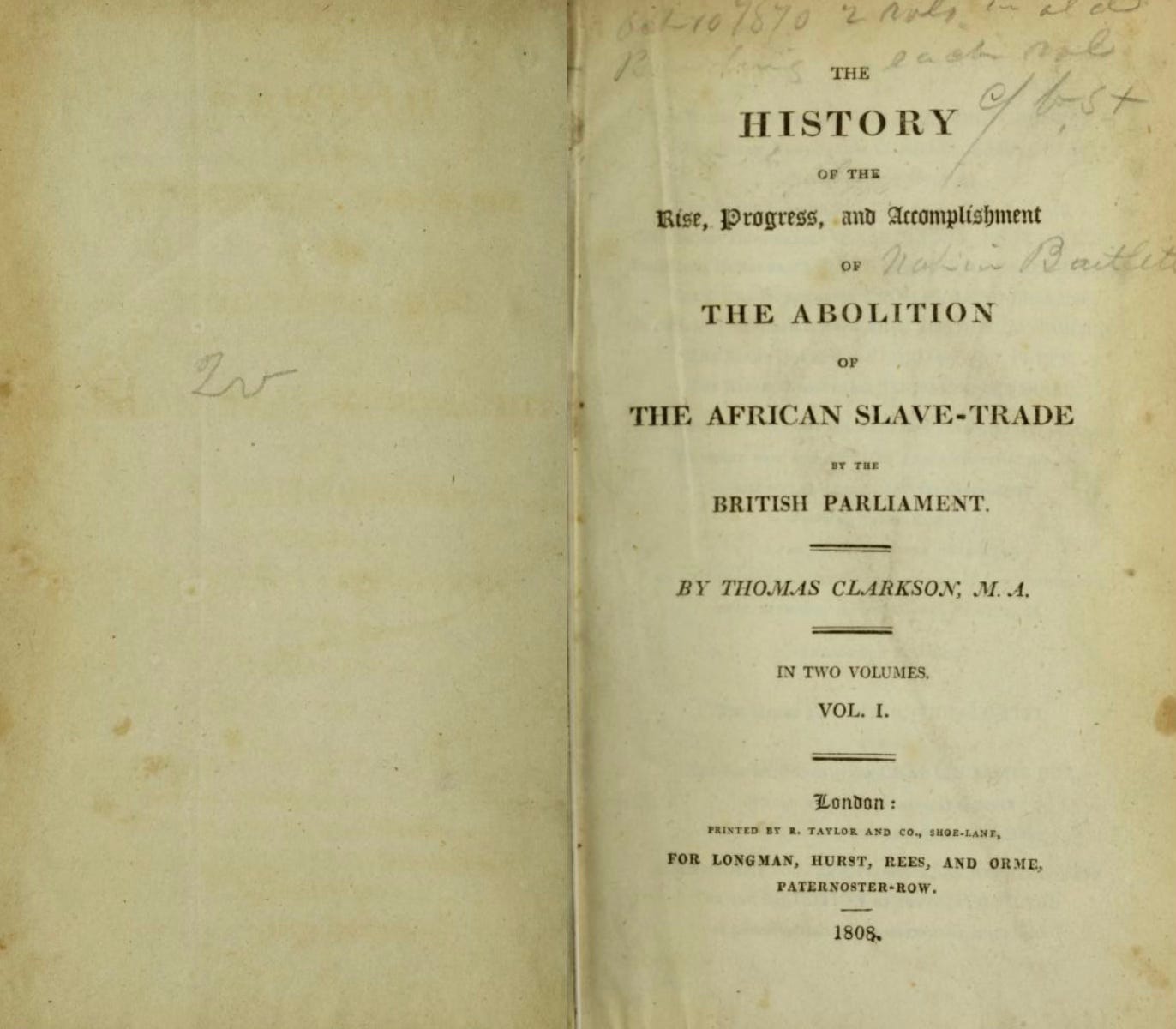

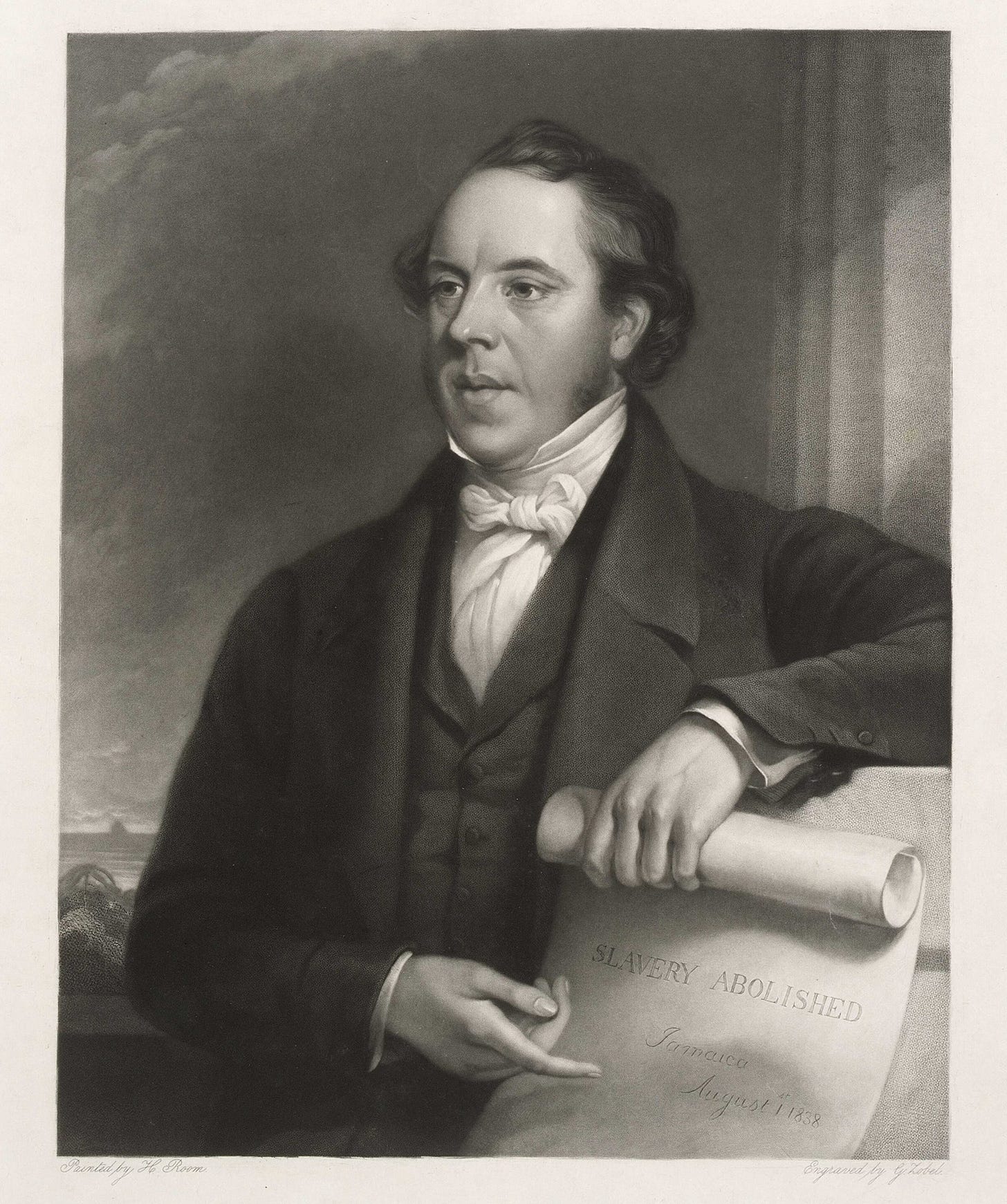

The Swedish King Gustav III took the lead in obscuring the Swedish slave trade. This is made clear in The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the Slave Trade by the British Parliament (1808), written by the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson.

Clarkson described a dilemma faced by anti-slavery campaigners in Britain: even if they succeeded in outlawing the slave trade at home, other nations might continue it. Sweden was one of the countries they feared would fill the gap.

To prevent that, Clarkson’s committee enlisted the Swedish naturalist and abolitionist Anders Sparrman to deliver a collection of British books on slavery to King Gustav III, hoping to persuade him to forbid Swedish participation in the trade.

According to Clarkson, the king responded that he had merely inherited Saint Barthélemy from France and that the island had already been populated by enslaved Africans. He claimed to be aware of their suffering but insisted that, to his knowledge, no Swedes were involved in the trade. He promised to do everything in his power to ensure that remained the case.

But Gustav III’s assurances were outright lies. Several years earlier, he and his royal council had granted a charter establishing the Swedish West India Company, explicitly permitting participation in the slave trade.

What’s more, the royal family was the company’s largest shareholder, and Gustav III himself was personally involved in managing the colony’s affairs.

Further reading:

The History of the Rise, Progress And Accomplishment of the Abolition of the Slave-Trade by the British Parliament by Thomas Clarkson (1808)

Den svenska kolonin S:t Barthélemy och Västindiska kompaniet fram till 1796 by Ingegerd Hildebrand (1951)

Ön som Sverige sålde by Bengt Sjögren (1966)

Det kungliga svenska slaveriet by Göran Skytte (1985)

Svarta Saint-Barthélemy: Människoöden i en svensk koloni 1785-1847 by Fredrik Thomasson (2022)