Sweden’s Forgotten Role in the Slave Trade

Cabo Corso, St. Barthélemy and colonial amnesia

Until quite recently, both in Sweden and abroad, a comforting belief has persisted: that Sweden remained untouched by the crimes of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. It fit neatly into the romanticized image of Sweden as a moral beacon in a brutal world.

But in recent years, that myth has begun to unravel. The date October 9 has gained recognition as a day to remember the abolition of Swedish slavery – the day in 1847 when the last enslaved people on the Swedish colony of St. Barthélemy were finally freed.

New Sweden

Slavery was abolished in Sweden as early as 1335, but that didn’t prevent the kingdom from engaging in the slave trade elsewhere. One of its first colonial ventures was New Sweden, established in the 1630s in what is now Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

At least one enslaved African lived in the colony: Anthony Swart, who arrived aboard the ship Fågel Grip. The vessel had previously traveled through the Caribbean, where Swart was likely purchased. Swart is remembered today as the first named enslaved African in Delaware’s history.

Economic troubles soon weakened the colony, and by the 1650s, Sweden lost it to the Netherlands. But that did not end Swedish ambitions overseas.

Cabo Corso

In 1645, the Walloon-Swedish merchant and industrial magnate Louis De Geer had the idea of establishing an African colony. His eyes were set on the Gold Coast – modern-day Ghana – an area extremely rich in gold. He sought Queen Christina’s approval to establish the venture under the Swedish flag.

When the crown hesitated, De Geer took matters into his own hands. The following year, he dispatched a merchant ship to the coast of what is now Nigeria, where the crew purchased ivory and over two hundred enslaved Africans. The boat then crossed the Atlantic to the Caribbean, selling the survivors for sugar and tobacco – luxury goods in seventeenth-century Sweden.

When the ship returned to Gothenburg in 1647, the profits proved the trade’s potential. Among the cargo were four enslaved Africans, presented as gifts to the powerful Axel Oxenstierna, Lord High Chancellor of Sweden.

The success caught the crown’s attention. In 1649, after two more profitable voyages, De Geer finally received royal permission to form a trading company.

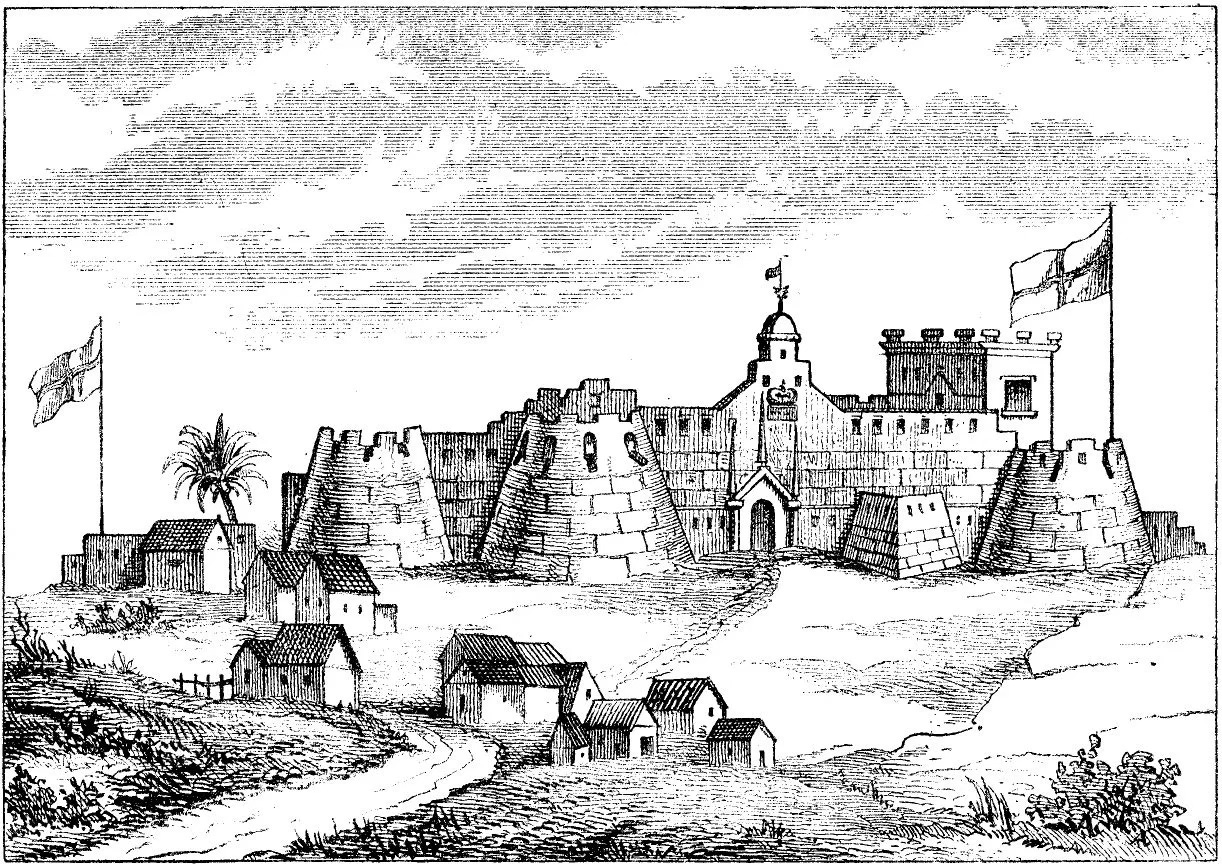

That same year, the Swedish Africa Company was founded. In 1650, it established the colony of Cabo Corso – today Cape Coast, Ghana – and soon seized a Dutch trading post, rebuilding it into a fortress called Karlsborg, in honor of Queen Christina’s successor, Charles X Gustav. Sweden was now ready to officially enter the transatlantic slave trade.

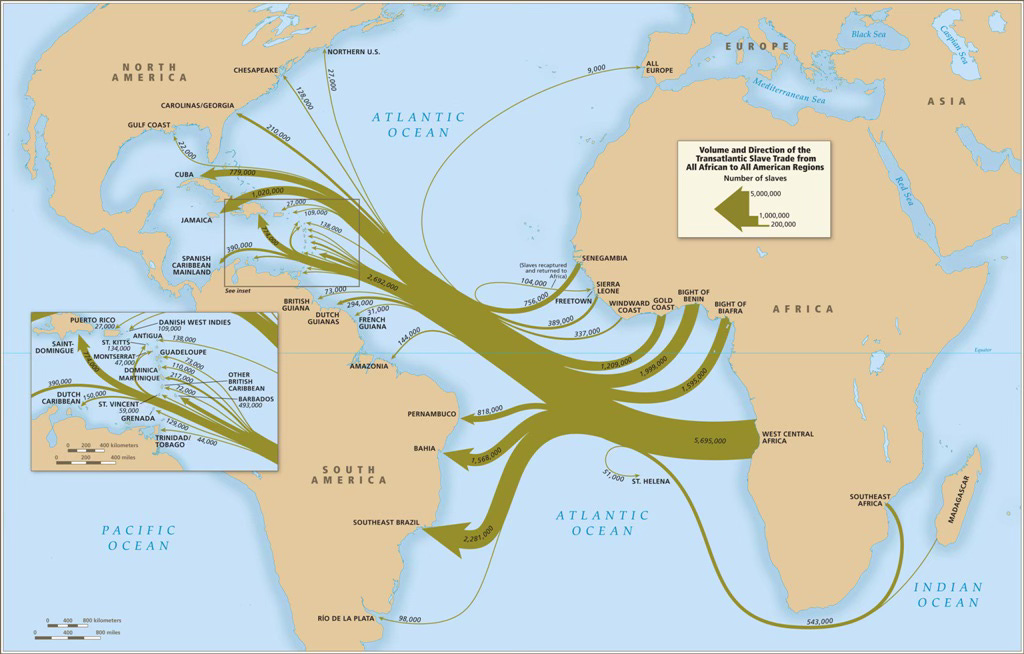

However, larger European powers fiercely guarded their colonial interests. After losing New Sweden, the Swedes no longer had a foothold in the Americas. Without their own plantations, they lacked a steady market for the enslaved people shipped from Africa and thus could not profit from the full “triangular trade.”

That triangular trade – ships leaving Europe loaded with weapons, textiles, and metals, exchanging them in Africa for enslaved people, transporting those people to the Americas, and returning to Europe with sugar, tobacco, rum, and cotton – was the engine of colonial wealth. But Sweden’s missing link in the triangle made it challenging to compete.

The Africa Company improvised. It began trading with the Portuguese colony on the island of São Tomé and Príncipe, off the coast of Gabon, whose sugar plantations needed enslaved labor. In the 1650s, enslaved people from Karlsborg were shipped there in exchange for sugar and other goods.

By 1657, the Company had signed a contract to deliver 500–600 enslaved people to the Dutch colony of Curaçao.

The lure of wealth led to fierce competition along Africa’s west coast. European powers fought for control of the many slave forts lining the beaches – including Karlsborg, which repeatedly changed hands between the Danes, Dutch, and English. Sweden managed to hold it for only thirteen years before being forced out in 1663.

Blood Metals

Even after losing its African foothold, Sweden continued to profit indirectly from the slave trade. By the 18th century, Sweden had become Europe’s leading exporter of “voyage iron” – iron bars standardized in size, weight, and marking.

Ironworking had deep roots in West and Central Africa, where metal tools and weapons had been produced locally for a long time. However, new industrial techniques in Europe significantly increased output, making imported iron cheaper and more abundant. As a result, ”voyage iron” became a key currency in the buying and selling of enslaved people

Other forms of Swedish iron were equally sought after. It had many uses, including the crafting of rifle barrels and the shackles that bound enslaved people during transport.

Saint-Barthélemy

The failure of Sweden’s first colonial venture, Cabo Corso, did little to discourage further ambitions. Just over a century later, Sweden tried again – this time in the Caribbean, on the small island of Saint-Barthélemy.

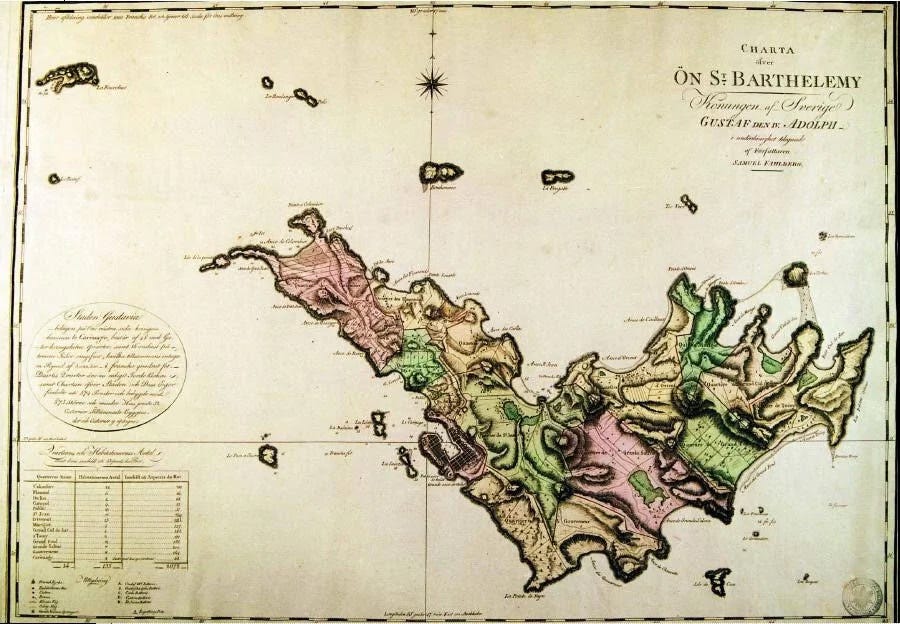

Originally colonized by France in 1648, the island was ceded to Sweden in 1784 in exchange for free trading rights in Gothenburg. Although picturesque, Saint-Barthélemy had little to offer in terms of natural resources or fertile land, making large-scale plantations impossible. Instead, the Swedes decided to transform it into a free port – a neutral trading hub poised to profit from the turbulence of the post–American Revolutionary era, when new naval conflicts seemed imminent.

When Sweden took over, the island’s population numbered between 700 and 800 people – roughly a third were enslaved Africans, the rest free whites, primarily French.

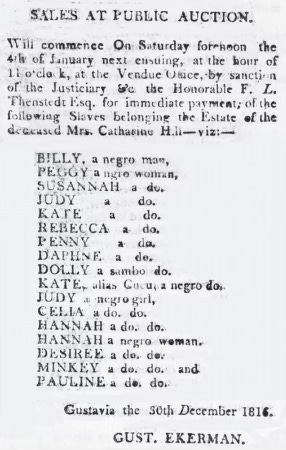

The slave trade was quickly woven into the island’s new economy. The 1790 tariff explicitly made the import of enslaved Africans duty-free.

Exporting enslaved people, however, was taxed – though Swedish ships paid only half the duty, an incentive meant to bolster Sweden’s role in the trade. Through a charter from King Gustav III, the Swedish West India Company received exclusive Swedish rights to conduct all commerce on the island.

When the first Swedes – initially merchants, then civil servants, and a small contingent of soldiers – arrived, they began constructing a new port town on the western part of the island. Both free whites and enslaved people were recruited to work on its construction. The settlement was named Gustavia, after Sweden’s king.

The island’s free port status soon attracted traders and fortune seekers, especially after the French Revolutionary Wars broke out in 1792. As Europe descended into a decade of war, Saint-Barthélemy’s neutrality became a magnet for commerce. By 1800, Gustavia had grown to around five thousand inhabitants, making it one of the most populous cities in the Swedish Empire.

Sweden’s rule did not improve conditions for the enslaved. In 1787, the Code Noir was introduced, dividing the population into whites, enslaved people, and “free colored people” – a term for Black individuals who had been freed or were born to free mothers. They were allowed to own property but denied the right to participate in politics. Today, the group is generally referred to as free Blacks, as the original label assumes whiteness as the norm.

The Swedish version of the Code Noir, approved by the Supreme Court in Stockholm, was essentially a copy of the French model. It set out rules for punishment, curfews, and movement, as well as social restrictions. Enslaved people continued to be imported from Africa and other Caribbean islands.

Since enslaved people legally owned nothing, punishments such as fines or imprisonment were not applied. Instead, corporal punishment was the norm. The most common was whipping with the so-called “negro whip”: victims were tied face-down between four poles and beaten across the back.

If the victim was a pregnant woman, a hole was dug in the ground to accommodate her belly – a gesture meant to “protect” the unborn child. Other punishments included branding, neck irons, and even execution.

It was also common for white men on the island to keep Black concubines. The mixed-race children born from these relationships were enslaved unless their fathers formally freed them. Freedom for free Blacks remained precarious – they could be re-enslaved for offenses such as sheltering fugitives.

The Code Noir also forbade them from carrying weapons, practicing medicine, or even holding weddings or social gatherings without permission from the Swedish military commander. They were “free,” especially compared to the enslaved, but they still faced intense discrimination.

Decline of the Swedish Colony

For a brief period, Saint-Barthélemy flourished. However, the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Anglo-American War of 1815 brought about significant changes. In times of peace, a neutral trading port was far less profitable.

Over the following decades, hurricanes and fever epidemics devastated the island, killing hundreds and destroying buildings. What had once been envisioned as a source of wealth for Sweden became a financial burden.

Meanwhile, the abolition movement was gaining strength across Europe. Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807 – though not slavery itself – yet on Saint-Barthélemy, human trafficking continued.

Sweden even sought to expand its presence in the Caribbean. In 1813, it briefly acquired the island of Guadeloupe, a major producer of sugar. But diplomatic negotiations following the Napoleonic Wars forced Sweden to return it just a year later.

After decades of British pressure, Sweden finally agreed to abolish slavery in 1845. Before doing so, however, the state had to compensate slave owners. It took two years to raise the necessary funds, and on October 9, 1847, all enslaved people on Saint-Barthélemy were freed. Many are believed to have left the island soon afterward.

Not everyone in Sweden supported the decision. In a speech to the House of Nobility, Count Johan August Anckarsvärd complained:

“The Estates have granted hundreds of thousands of riksdaler for the redemption of black slaves on Barthélemy, but they have never felt sorry for the fate of their white, tax-paying brothers here at home.”

The remark was quoted in Aftonbladet on December 7, 1847.

The End of Sweden’s Colonial Era

In the following years, the island declined. Poverty deepened, public buildings decayed, and residents emigrated in large numbers. By the 1870s, Saint-Barthélemy had become a drain on Sweden’s treasury.

In 1877, publicist Hugo Nisbeth visited the colony on behalf of the Swedish Ministry of Finance. He reported on widespread misrule, noting that governors had lived “as noble gentlemen” while neglecting the population. His findings, published in the Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfarts-Tidning, urged reforms to prevent the island from becoming a “dying colony” and instead transform it into a “rich and glorious paradise.”

But it was too late. That same year, Sweden reached an agreement with France – Saint-Barthélemy’s original colonial ruler – to return the island. A referendum sealed the deal: out of more than 2,000 residents, only around 350 voted, and just one person wished to remain under Swedish rule. On March 16, 1878, the handover was completed, marking the end of Sweden’s colonial era.

Remembering a Forgotten History

Sweden never became a major player in the transatlantic slave trade – its share of the total trade was minuscule. Yet the ambition was real. As historian Fredrik Thomasson notes in the acclaimed Svarta Saint-Barthélemy: Människoöden i en svensk koloni 1785-1847:

“What saved Sweden from participating in the worst crimes of slavery was its failure to participate in the, of hunger for profit, cruelty of plantation agriculture. However, Sweden’s ambition was to participate in the plantation economy, and attempts to obtain additional colonies continued into the nineteenth century. When Sweden was awarded Guadeloupe by Britain in 1813, there was great enthusiasm, and had Guadeloupe remained Swedish, Swedish slavery would have turned out differently.”

Despite growing awareness, Thomasson argues that a double colonial amnesia still prevails – a forgetting of both Sweden’s abuses against Black populations and its failed colonial ambitions.

That is why October 9 remains such an important date: a reminder that Sweden’s past, too, was entangled in the global systems of slavery and colonialism – and a call to make it an official day of remembrance.

Further reading:

Books:

Den svenska kolonin S:t Barthélemy och Västindiska kompaniet fram till 1796 by Ingegerd Hildebrand (1951)

Ön som Sverige sålde by Bengt Sjögren (1966)

Det kungliga svenska slaveriet by Göran Skytte (1985)

Africans in New Sweden: The Untold Story by Abdullah R. Muhammad (2013)

”Den svenska slavhandelns fader” by Mats Granberg for Norrköpings Tidningar (July 17, 2014)

Svarta Saint-Barthélemy: Människoöden i en svensk koloni 1785-1847 by Fredrik Thomasson (2022)

Scholarly articles:

”Foreign Markets for Swedish Iron in the 18th Century” by Karl-Gustaf Hildebrand i Scandinavian Economic History Review (vol. 6, nr 1, 1958)

”32 piskrapp vid quatre piquets. Svensk rättvisa och slavlagar på Saint Barthélemy” by Fredrik Thomasson in Historielärarnas förenings årsskrift (2013)

”’Voyage Iron’: An Atlantic Slave Trade Currency, its European Origins, and West African Impact” by Chris Evans and Göran Rydén in Past & Present (vol. 239, nr 1, 2018)

Articles:

Article without headline on page 2 of Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfarts-Tidning (March 8, 1877)

”Det svenska slavjärnet” by Jan Lönn for Dagens Nyheter (November 13, 2007)

”Sveriges slavhistoria avslöjad” by Niklas Zachrisson for svt.se (October 7, 2013)

”När Sverige skulle bli kolonialmakt” by Hans Norman for Populär Historia (March 14, 2001)

”Slavhandeln lyfte Sverige” by Maria Ripenberg for Upsala Nya Tidning (October 6, 2014)

”Sveriges omstridda strategi – i avskaffandet av slavhandeln” bt Martin Schibbye för Blankspot (June 25, 2020)

Other:

Handelskompanier och kompanihandel: Svenska Afrikakompaniet 1649–1663: En studie i feodal handel” by György Nováky (1990)

”Svensk handel med slavar 1784–1847. Varför infördes och avskaffades slaveriet på den svenska kolonin S:t Barthélemy” by Martin Schibbye at University of Stockholm (2007)

”Svenska järn- och stålindustrins historia” by Jernkontoret (November 21, 2018)