Trump’s Imperial Moment

How the Donroe Doctrine cartoon reveals a U.S. that no longer feels the need to justify power, plunder, or conquest.

In the days following the United States’ illegal military intervention in Venezuela, a barrage of statements poured out of Washington.

“The Cuban government should be concerned,” warned Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

“The world is governed by strength, force, and power,” declared Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller.

“We need Greenland,” President Donald Trump repeated, almost casually.

The men in the White House appeared pleased with themselves, almost giddy – clearly intoxicated by the question of what else they might be able to force through at gunpoint.

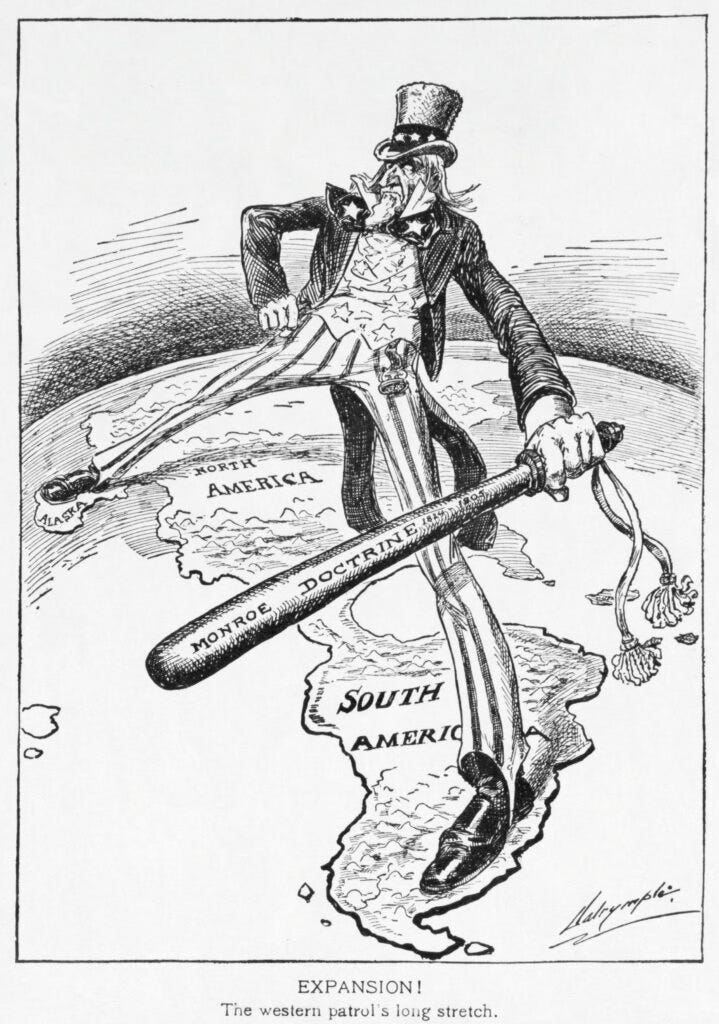

But one of the more revealing statements slipped through in the form of a tweet. On X, @TrumpWarRoom, an account linked to the administration, posted a cartoon of a gigantic Trump towering over the Americas – from Canada in the north to Argentina in the south. In one hand, he grips a baton inscribed with the words “The Donroe Doctrine.” Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth then reshared the post.

The reference was anything but subtle. The cartoon is a nod to Louis Dalrymple’s classic early-20th-century illustration, circulated in satirical magazines such as Puck and Judge. In Dalrymple’s version, it is Uncle Sam who dominates the hemisphere, legs outstretched, holding a baton labeled “The Monroe Doctrine.”

That doctrine – issued in 1823 by President James Monroe – originally framed European involvement in the Americas as unacceptable. What began as an ostensibly anti-colonial position soon hardened into something else entirely: a declaration of American supremacy over the Western Hemisphere.

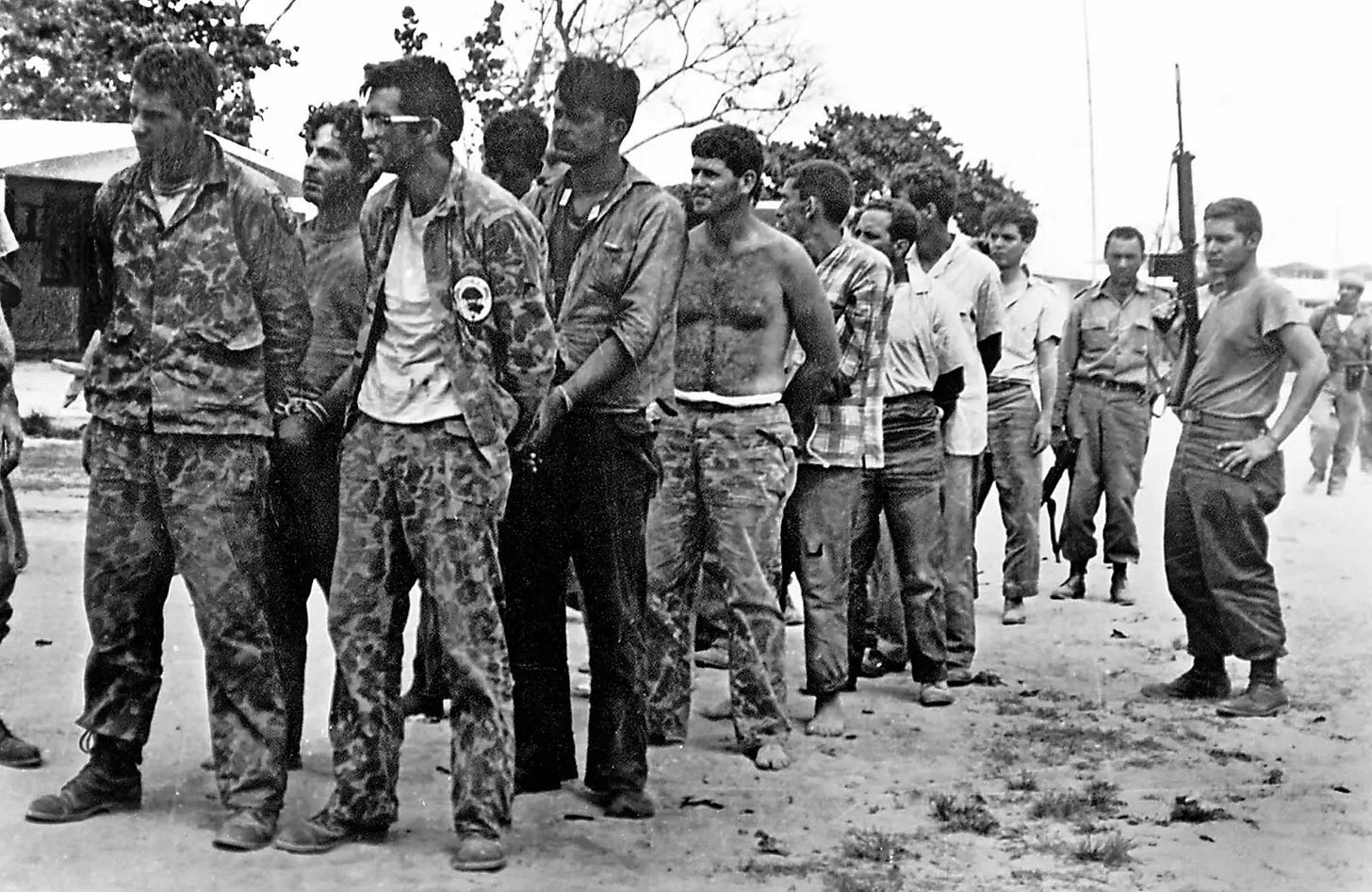

Anyone who believes the intervention in Venezuela represents a new geopolitical direction must either be naïve or profoundly ignorant of U.S. history in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. This is not a departure; it is a return. A return to a time when Washington openly regarded the region as its backyard, where leaders could be overthrown or installed at will, tribute extracted, and the rules dictated without apology.

What is new is how little the Trump administration feels compelled to disguise its intentions. Gone is the familiar rhetoric of democracy promotion or anti-communist crusades.

To be sure, preventing increased Chinese influence in South America is still muttered in the background, largely out of habit. And the attempt to rebrand the kidnapping of Venezuela’s controversial president, Nicolás Maduro, as a “law enforcement operation” – a legally legitimate police action – convinces no one. Vladimir Putin, who insists on calling the war in Ukraine a “special military operation,” would surely admire the terminology.

Instead, Trump has been unusually blunt about what this is really about: oil. He’s interested in natural resource extraction, not free elections, civil liberties, or a free press. If democratic values were truly the concern, Trump could hardly defend his intimate ties to oil-rich Gulf monarchs or his warm relationships with autocrats such as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Viktor Orbán.

In recent days, Trump has gone further still, announcing that Venezuelan oil will now be delivered directly to the United States, with the proceeds controlled by him. In an interview with Fox News host Jesse Watters, Vice President JD Vance doubled down on the message.

The takeover of Venezuela, he argued, benefits ordinary Americans because it gives the United States “control over Venezuela’s incredible natural resources,” ensuring that “Americans will always have access to high-quality, cheap energy.”

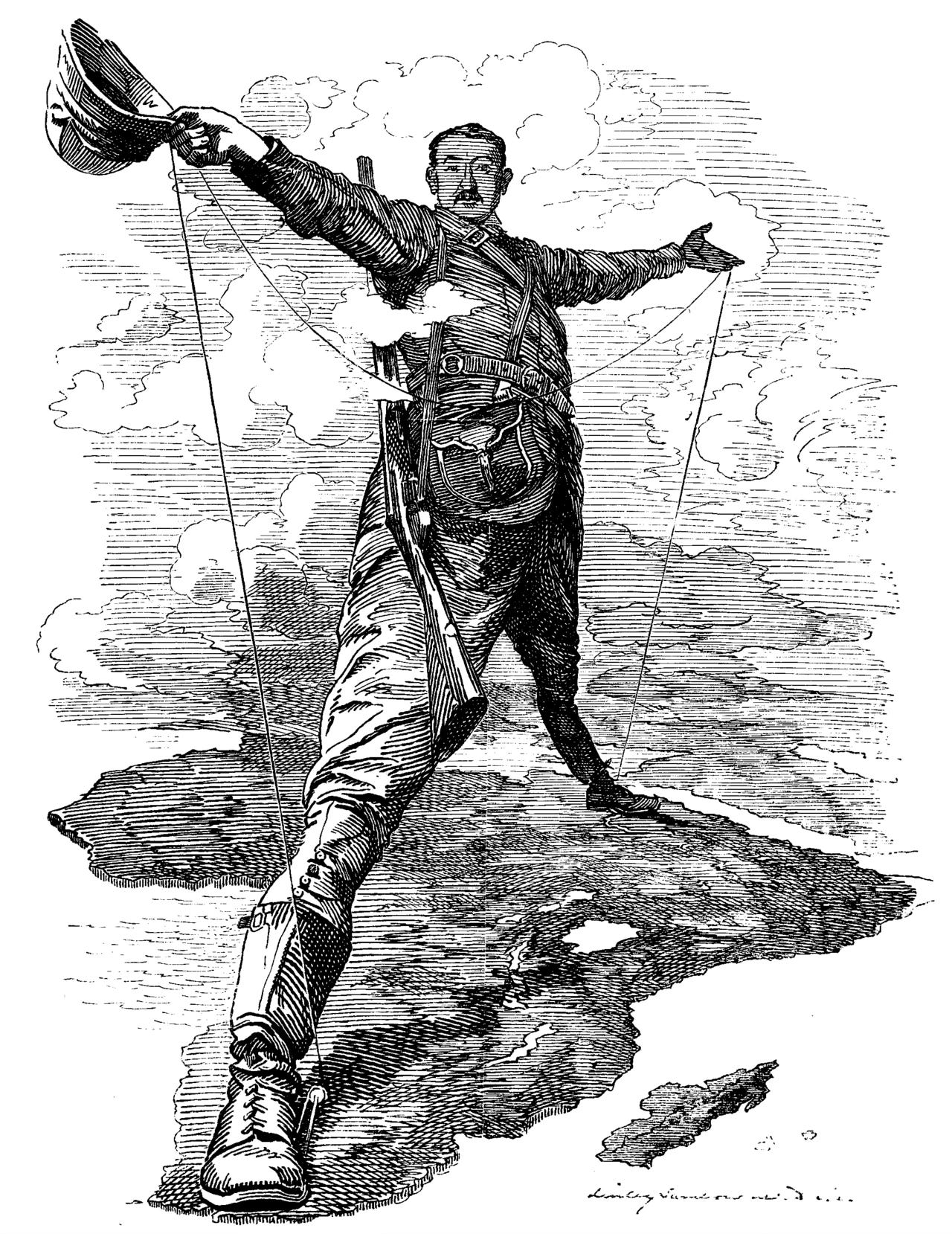

Trump’s posture recalls that of the British industrialist Cecil Rhodes, who was depicted like Trump and Uncle Sam in a strikingly similar cartoon as early as 1892.

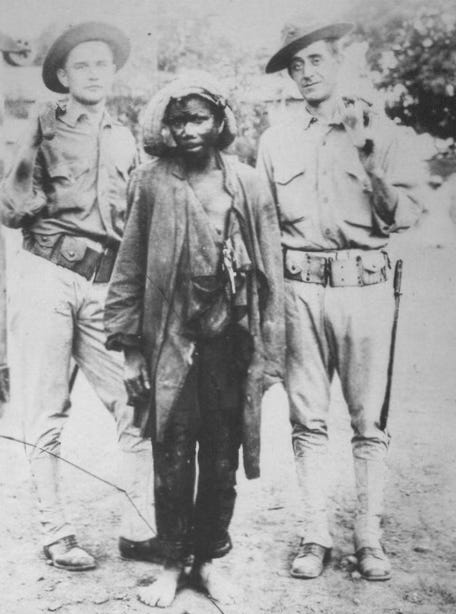

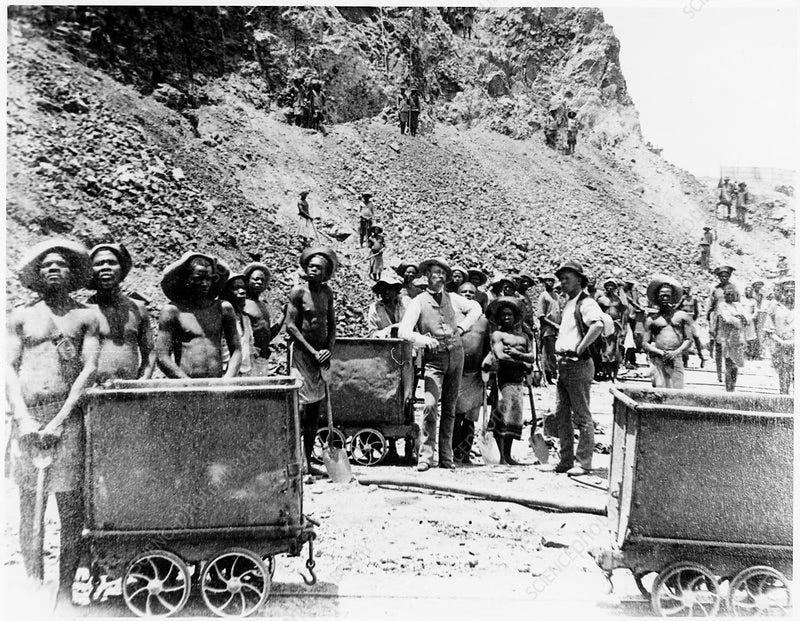

But where Trump looms over the Americas, Rhodes stretched across Africa. The illustration – published in the satirical magazine Punch – showed Rhodes bestriding the continent, envisioning a continuous railway and telegraph line linking Britain’s African possessions from Egypt to South Africa. It was the visual manifesto of his ambition to bring “civilization” to a continent he and his contemporaries regarded as populated by “savages.”

But more than anything, Rhodes was motivated by raw extraction. In the 1870s, he threw himself into South Africa’s gold and diamond rushes. Through a series of dubious deals and ruthless consolidation, his company, De Beers, came to dominate the global diamond industry.

Like Trump, Rhodes was a businessman who then leveraged his wealth into political power, eventually ruling over entire territories: first the British Cape Colony, and later the colony he founded himself: Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe.

The illustration known as The Rhodes Colossus appeared at a moment when Britain no longer felt the need to justify or apologize for its empire. Imperial dominance was a fact, and there was no rival strong enough to challenge it meaningfully.

The Trump administration’s casual circulation of the Donroe Doctrine image signals something similar. The United States, it seems, has largely abandoned its previous charade. Less and less time is spent constructing moral justifications. More and more openly, the administration asserts that as the world’s most powerful nation, it has the right to seize the Panama Canal, demand minerals from Ukraine, annex Greenland, and, in short, trample the rest of us.

One of the lessons of the 21st century is that the label “terrorist” functions as a master key. Once applied, it unlocks every conceivable method of repression: mass surveillance, arbitrary detention, imprisonment without trial, even torture. All of it is rendered legitimate in the name of combating terrorism.

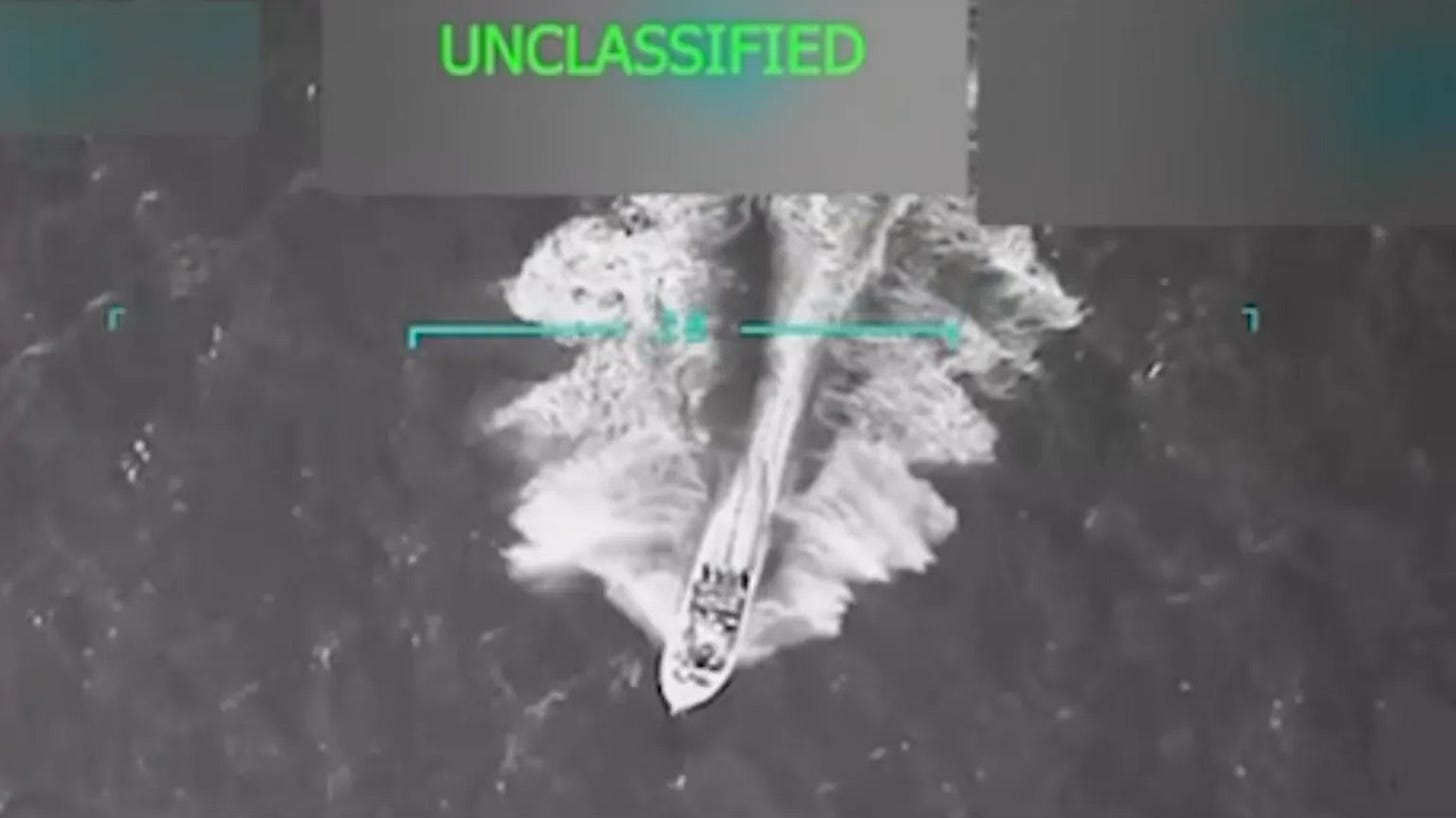

That Nicolás Maduro would ultimately meet this fate was therefore entirely predictable. The groundwork had been laid – from branding Venezuela a sanctuary for “narco-terrorists” to issuing executive orders that redefined fentanyl as a weapon of mass destruction. These steps formed a three-stage rocket: first, the destruction of alleged drug boats in the Caribbean, then the hijacking of oil tankers, and finally the removal of Maduro himself.

A straight line runs from the Rhodesian Colossus to the Monroe Doctrine to the Donroe Doctrine: three images from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, each illustrating the same principle: the right of the strong to rule and plunder as they please.

Despite what Trump’s defenders insist – that his threats are merely rhetorical, that he is playing some unfathomably sophisticated game – it is long past time to take him at his word. His administration truly sees itself as a global overlord. The rest of the Americas, and by extension, the rest of the world, is simply something beneath its feet.