Thomas Sankara and the Stolen Revolution

This is the story about a country where corruption was rampant, where a small elite lived well at the expense of the majority, and where international aid was essential for survival.

It is also a story about a person who wanted to change that. The methods were questioned, but the result spoke for itself.

This is the story of Thomas Sankara and his struggle to make Burkina Faso stand on its own two feet. A fight that cost him his life.

October 15, 1987

They sit around the table, as they've done countless times. On the agenda is a discussion of a new revolutionary code of conduct to combat corruption. The cabinet members engage in their usual banter before one of them declares the meeting officially open.

But the order is suddenly disrupted by the commotion outside. A skidding car, frantic voices, and machine gun fire compete for attention. Panic engulfs the room, chaos ensues, and instinctively, the men dive for cover. But then one of them stands up.

Thomas Sankara.

The mastermind behind the revolution. He had fundamentally changed Burkina Faso in just four short years.

Sankara stands up slowly and meets the eyes of the others, one by one. "Stay here," he says. "It's me they want." Then he carefully inches towards the door and opens it. He raises his arms above his head and walks out. Moments later, another round of machine gun fire rings through the building.

As Thomas Sankara lies motionless on the floor, his body pierced by bullets, he's only 37 years old. Under his leadership, Burkina Faso saw tremendous development, making rapid strides toward freeing itself from the shackles of corruption. But his radical and swift changes were not appreciated by everyone. Enemies lurked within his borders and among the powerful forces of the Western world.

Now, one central question remained: Who murdered him? And why?

Long before Thomas Sankara, the Mossi kingdoms ruled the region that makes up today's Burkina Faso. It was a collection of loosely composed states that held sway over the area ever since the 1200s. The Mossi people make up more than half of Burkina Faso's population even today.

However, the Mossi kingdoms' reign was shattered in 1896. Formidable French forces descended upon the land, signaling the beginning of a fierce struggle.

The clash between invaders and resilient locals continued for years. But in 1919, the final blow fell, and France transformed the land into a colony known as French Upper Volta. The name alluded to the upper reaches of the Volta River, which flows through the country.

It's a beautiful region with majestic baobab trees and vast plains of the distinctive red earth. But it is simultaneously a crucible of inhospitable elements, where searing heat, recurring droughts, and scarce water supplies conspire to make life hard for many. The country's northern parts lie in the Sahel zone, where the mighty Sahara desert transitions to sweeping savannah and grass plains. During the most challenging periods, the margins for survival are thin.

The colony was of low priority to the French, who primarily used it as a source for limited cotton production and a steady supply of cheap labor. Forced labor, high taxes, and the use of violence by colonial masters were commonplace. Poor farmers had their grain requisitioned by the state. And the French recruited scores of young men to build infrastructure in what they deemed more important colonies, such as the Ivory Coast.

The independence

But increased demands for self-government followed in the aftermath of World War II. And in the 1950s, France, compelled by the shifting tides of time, took decisions that, step by step, made it possible. In 1960, the country became independent.

Maurice Yaméogo, who had a lengthy background in the colonial administration and had long belonged to an elite class of, if you will, Europeanized Africans, was named the nation's first president.

But his political maneuvers in the run-up to independence effectively turned him into an autocrat. Upper Volta, as the country was now called, thus began its independence as a de facto dictatorship.

Immediately, corruption began to slither into the very fabric of society, with Yaméogo leading the charge. Despite the country's highly strained economy, he embezzled large sums of money. He spent millions on expensive cars and luxury homes. Nepotism became the norm, as coveted positions were gifted to family members, all while he jailed his critics.

In 1965, fresh from his so-called "re-election" with a staggering 99.97 percent of the vote, he married the twenty-two-year-old Miss Ivory Coast contest winner. The opulent ceremony, a monument to excess, soured the people's hearts. The president, still wedded to his first wife, became a symbol of unbridled power and unapologetic hubris.

Raised taxes, suspended benefits, reduced wages for government employees, and reduced veteran pensions – all while Yaméogo spent money on a new presidential palace – helped spark a general strike in early 1966. Unions, students, city dwellers, and the religious elite rose against Yaméogo.

Caught off guard, he responded with a heavy hand. He declared a state of emergency and threatened the strikers with military force. But instead, the very soldiers tasked with enforcing his rule turned against him. Yaméogo suddenly found himself compelled to step down, his reign crumbling beneath him.

A series of coups

In retrospect, we know that Africa has suffered from the many armies that seized power across the continent. But this was a more innocent time. Here, people still believed that the military, with its discipline and structure, was precisely what was needed to overcome the politicians' wallowing in excesses and corruption.

As a result, the population widely supported the military's takeover, and many assumed that, after a transitional period, the army would return power to the people.

For the inhabitants of Upper Volta, however, it soon became apparent that this was only the beginning of a series of revolts that would succeed each other in the coming decades. First, Lieutenant Colonel Sangoulé Lamizana installed himself as president. He served until 1980, when Colonel Saye Zerbo overthrew him in another military coup. Zerbo only managed to rule for barely two years before he, too, was deposed, this time by Major Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo.

The next coup took place in 1983. But this one was different from the others. For now, a man with grandiose visions for Upper Volta came to power.

Thomas Sankara’s rise to power

Thomas Sankara was born in 1949 in the small town of Yako in the northern parts of French Upper Volta. He spent his childhood in Gaoua, near the border with Ghana and the Ivory Coast, where his father was part of the gendarmerie, a militarily organized police force.

As the colonial power employed his father, the family had a relatively privileged position. They lived in a brick house up on a hill above the city, together with the other families of the gendarmerie. The family also stood out by being Catholic in a country where most were Muslim.

School became an eye-opener, where social boundaries blurred, and Sankara mingled with peers from diverse backgrounds. He saw how impoverished some of the students from the lower social classes were and noted how favorably the children of French officials were treated.

As the eldest son of what eventually became eleven children, Sankara's position within the family hierarchy granted him a mantle of responsibility. His parents gave him more space to express his opinions. They asked him to take on a leadership position: they gave him the responsibility of raising and educating his younger siblings, who in turn began to see him almost as an extra parent.

Sankara was a good student, especially in French and mathematics. At seventeen, he entered the newly established military college in Burkina Faso's capital, Ouagadougou.

There, his horizon expanded. In addition to military training, he was educated in several academic subjects. He got to know young minds destined for leadership. But perhaps the most important person was history and geography teacher Adama Touré, who introduced him to concepts such as neo-colonialism, imperialism, communism, and socialism. Sankara's eyes widened.

In 1969, Sankara became among the few students selected to continue his education at the military college in Antsirabe, Madagascar. There, he supplemented his studies with agricultural knowledge, read Karl Marx for the first time, and witnessed the protests against the pro-French regime that shook the country in 1972.

The following year, Sankara's return to his homeland was marked by war. An armed border conflict erupted between Upper Volta and Mali in December 1974, and he found himself immersed in the chaos. Commanding a squad, he successfully participated in one of the few battles in the otherwise uneventful war.

The press hailed him as a war hero, but Sankara shunned such titles. Instead, he was struck by the senselessness of the conflict. How it affected ordinary civilians, people who had most things in common but had ended up on opposite sides of a colonial land border, and now had their lives torn asunder as a result. In the meantime, however, he became close friends with another distinguished soldier, Blaise Compaoré, and gained a reputation as an officer of great promise.

President Sangoulé Lamizana – the man who had seized power in a coup d'état in 1966 – recognized Sankara's potential and entrusted him with a crucial task. In 1976, he appointed Sankara to lead a new military camp in the town of Pô. There, elite troops would be honed and shaped, ready to confront the challenges ahead.

Within the camp's confines, Sankara transformed into a beloved figurehead. He ignited a passion for knowledge among his soldiers, urging them to read more books. He mobilized them to help local villagers with various construction projects. He also played guitar in a jazz band with his trusted companion Compaoré.

Sankara's influence extended further as he took the stage to deliver impassioned lectures on social issues. He even orchestrated outdoor film screenings, set up accounts for the soldiers at a local bank, and taught them how to manage their money. Usually, military leaders ate separately, but Sankara ate together with his soldiers, who slowly but surely began to adore him.

But simultaneously, Sankara became increasingly concerned about the country's many challenges. The population was poor, literacy was low, and corruption was high. Food prices soared while those who had the means embezzled everything they could. Some even pillaged aid shipments meant to combat famine, lining their pockets at the expense of the desperate.

So when Colonel Saye Zerbo seized the reins of power in a military coup in 1980, Sankara greeted the new regime with cautious optimism, hopeful that the promises of progress would materialize. However, a nagging doubt lingered in his mind – a flickering suspicion that the leadership lacked the audacious vision required to usher in true transformation in the country.

Sankara's ascent continued unabated. First propelled to the rank of captain, he then found himself catapulted into the realm of even greater influence as he assumed the role of information minister in September 1981. Reluctantly accepting the position, he was torn between aligning himself with an uncertain regime.

In actuality, he had no choice: to be Minister of Information was not so much a job offer as a military order. As a soldier, he had to follow it. However, Sankara set his conditions: the tenure would only be temporary, and in the meantime, the command of the military camp would pass on to his dear friend, Compaoré.

In the corridors of power, Sankara stood out. On his bicycle, he pedaled to work through the bustling streets, leaving his government car behind. He often ate at one of the cheap lunch counters lining the streets. He even urged the press not to idealize the government in their reports.

But despite the government's promises to the contrary, corruption and repression continued to be part of the new regime. The right to strike was outlawed, student activists were imprisoned, and unions faced opposition.

Disgusted by these abuses of power, Sankara abruptly resigned in April 1982, after a mere six months in office. He announced his decision in a live radio appearance, accusing the government of silencing the people. The regime swiftly retaliated, stripping him of his captain's rank and exiling him to a secluded military camp in the remote western reaches of the nation.

But the days of Saye Zerbo's regime were numbered. In November 1982, the army seized the capital, paving the way for a new military junta led by new President Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo.

Sankara's unwavering popularity had caught the collective eye, and in January 1983, Ouédraogo offered him the prestigious post of Prime Minister. However, their visions clashed, and the relationship quickly strained due to Sankara's demands for a more progressive policy. Armed with fiery speeches that drew fervent young crowds, Sankara unleashed scathing criticisms upon the bureaucracy, middle-class entrepreneurs, and the political elite.

Within the junta, a clear divide emerged between the older guard, nurtured under French tutelage, who clung to remnants of the colonial era, and the younger, more radical generation who saw imperialism and neo-colonialism as the root cause of their nation's woes.

The Non-Aligned Movement was an organization for states in the so-called Third World. It sought to guard the interests of member states during the Cold War battle between East and West. In March 1983, the organization held a conference in New Delhi, India, and Sankara was one of the speakers. This was his grand debut on the international stage, and he seized the opportunity.

He came out as an opponent of Israel's invasion of Lebanon, criticized US imperialism in South America, and voiced his unwavering support for the oppressed people of apartheid-stricken South Africa.

During the pivotal conference, he had a long conversation with Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Before the conference, Sankara had visited Libya, and after it, he quickly visited North Korea.

These encounters fueled the concerns of the Western powers, who fretted that this charismatic young leader could steer Upper Volta towards the path of socialism or perhaps even veer into the realm of unabashed communism.

At home, however, Sankara's conviction and magnetism continued to captivate the hearts of his people. Yet, his revolutionary ideals stoked fear in the heart of President Ouédraogo, who viewed him as a potent threat to the status quo. Unbeknownst to the president, Sankara invited the infamous Libyan dictator, Muammar al-Gaddafi, to visit Upper Volta even though both the United States and France viewed Gaddafi as a villain.

A little over two weeks later, Sankara was arrested and placed under house arrest. Some historians have argued that this was due to pressure from France. The regime believed that capturing Sankara would restore political stability and quell the country's revolutionary elements. But they gravely underestimated the impact of their actions. The decision unleashed a furious storm of anger amongst the people and the country's young officers, igniting wild protests.

On August 4, Captain Blaise Compaoré, Sankara's loyal friend, led troops toward Ouagadougou. They captured the capital with minimal resistance. As the evening approached, people stopped in their tracks as they heard Sankara's voice on the radio.

He announced the removal of the military junta and the creation of the National Revolutionary Council, the country's new ruling party. Sankara, only thirty-three years old, assumed the presidency himself.

The next day, jubilant crowds flooded the streets. August 5 – Upper Volta's Independence Day – was now forever intertwined with the birth of the revolution. It was a deliberate move. Sankara rode through the town, his presence a beacon of hope, periodically stopping to engage with residents whose faces radiated eager anticipation.

As the dust settled and the cheers subsided, Upper Volta stood on the precipice of colossal change.

A new type of revolution

The previous coups d'etats had merely shuffled the deck of power. But Thomas Sankara's revolution had real ambitions to create a new order in the country.

High on the agenda was dismantling the entrenched corruption ensnaring Upper Volta, where a privileged few reveled in opulence while the majority languished in poverty. In the book Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary, American journalist Ernest Harsch quotes a speech Sankara gave two months after the takeover. In it, he described Upper Volta's 23 years of independence as a:

"Paradise for the wealthy minority, for the majority – the people – it is barely a tolerable hell."

Sankara's promises were many and grand. But the challenges were extreme. The World Bank ranked Upper Volta as one of the world's poorest countries, and foreign investment trickled in at a feeble pace. To compound the struggle, the population relied almost exclusively on agriculture, their livelihoods often impacted by droughts, severe floods, and voracious locust swarms.

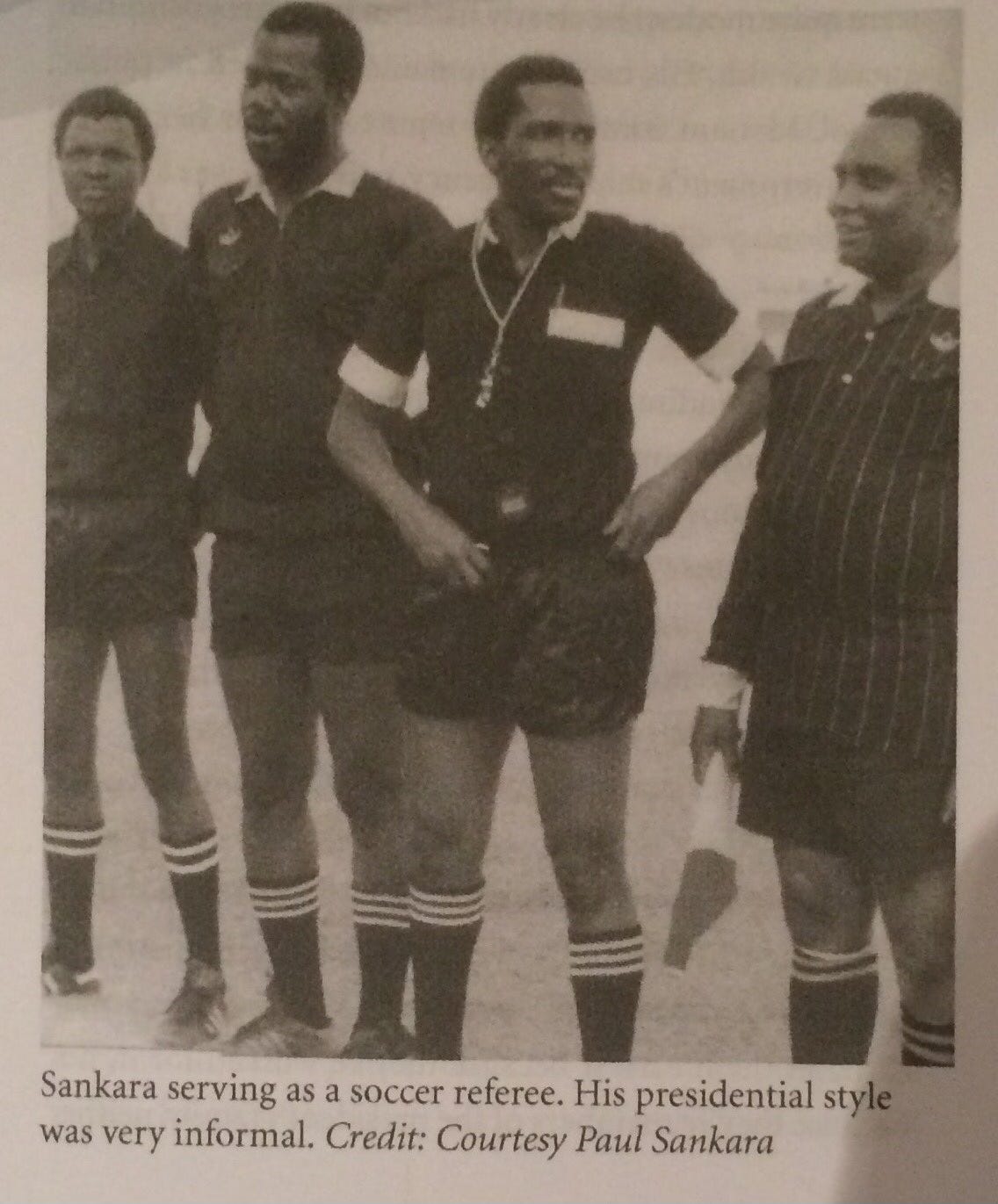

True to his nature, Sankara's informal leadership style broke the prevailing trend among many contemporary African leaders. He did not allow pictures of himself in public buildings or places; he continued to live in the same simple house as before, his two children went to a government school, and he avoided giving relatives favorable treatment. His wife Mariam continued to work at a shipping company while his mother worked in the market.

On the anniversary of the coup, Sankara changed the country's name from the colonial Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, which in local languages roughly translates to "land of the honorable." As a somewhat of a guitar player, he wrote the new national anthem himself.

Sankara then launched several ambitious projects. He had the government's collection of expensive Mercedes cars sold and bought much cheaper Renault 5 models instead. The money left over from the sale he instead spent on schools and health clinics.

He gave government employees, including himself, modest salaries and banned them from traveling in first class. He had several special bonuses relinquished that once adorned the pockets of politicians and government employees. In Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa, historian Brian J. Peterson writes:

"In contrast with many governments that resorted to austerity measures at this time – usually by cutting health care, education, and other social programs while preserving the privileges of elites – Sankara did quite the opposite, forcing elites to make sacrifices and ensuring that austerity helped the rural poor."

In the wake of the transformative coup that thrust him into power, Sankara ignited a call to action, urging the people to forge so-called "committees for the defense of the revolution." These collectives, CDRs, drew inspiration from the Cuban model, initially serving as defenders of the new order.

Armed with simple tools and basic training, the new government tasked ordinary citizens with watching for potential counter-revolutionaries. But soon, the CDRs evolved into vehicles of mobilization, a way to implement the government's directives. Their ranks consisted of individuals from all walks of life, from the well-educated to the illiterate, and they arrived at their decisions by vote.

The sweeping responsibilities bestowed upon the CDRs knew no bounds: from building and repairing roads to distributing food to those in need. Everywhere, communities banded together, harnessing the strength of their shared purpose, and took charge of developing the nation. They constructed schools, built housing, and dug new irrigation systems.

Among the rural Mossi population, authority had traditionally rested in the hands of elder male village chiefs – sometimes a person, sometimes a council. These leaders were accustomed to holding much power and had considerable self-determination.

But the winds of change swept through all corners of the nation, and the CDRs gradually usurped their roles. They became the tangible embodiment of the government at the grassroots level, both in urban areas and the farthest reaches of the countryside.

Sankara's vision extended beyond the realms of infrastructure. He sought to redefine Burkina Faso's society, breaking the traditional gender roles that had long relegated women to the sidelines. From a young age, Sankara observed the stark disparities between the treatment of men and women, an awareness nurtured by the influence of his mother and six sisters. Even as a nine-year-old, he had stepped forth and shielded his mother from his father's hand.

In a speech given by Sankara on International Women's Day in 1987, reproduced in full in the book Women's Liberation and the African Freedom Struggle, he said:

"While society sees the birth of a boy as a gift from God,' the birth of a girl is greeted as an act of fate, or at best, a gift that can be used to produce food and perpetuate the human race. The little male will be taught how to want and get, to speak up and be served, to desire and take, to decide things on his own."

Then he compared it to how society raises women:

"The future woman, however, is dealt blow after blow by a society that unanimously, as one man – and "as one man" is the appropriate term – drums into her head norms that lead nowhere."

He continued;

"From the age of three, she must meet the requirements of her role in life: to serve and be useful. While her brother of four or five or six will play till he drops from exhaustion or boredom, she, with little ceremony, will enter the process of production. She already has a trade: assistant housewife. It is of course an unpaid position, for isn't it generally said that a housewife "does nothing"? Don't we write "housewife" on the identity cards of women who have no income, meaning they have no job? That they are "not working"? With the help of tradition and obligatory submissiveness, our sisters grow up more and more dependent, more and more dominated, more and more exploited, and with less and less leisure or free time."

Sankara outlawed female circumcision, polygamy, and forced marriage. He introduced a minimum age for marriage and decided on new rulings that made it so that divorce proceedings now had to consider a woman's consent. Widows, long marginalized, were granted inheritance rights.

He banned prostitution, calling it "nothing but a microcosm of a society where exploitation is a general rule". Women who had previously sold their bodies were offered places in rehabilitation centers where they received housing and vocational training, which was also provided to the homeless.

He also mandated that a minimum of 30 percent of government positions be held by women, amplifying their voices in decision-making spheres. Furthermore, his government granted pregnant girls and women the right to stay in school.

In a symbolic demonstration of the burdens women bear within the home, Sankara orchestrated a protest. In Burkina Faso, women traditionally went to the markets daily, bought the food, and carried it home.

But on September 22, 1984, the roles were reversed, and the men were forced into the markets to make them respect the workload and gain firsthand experience of the weight carried by women in their daily lives. It was an act aimed at challenging societal norms and fostering an appreciation for the contribution of women.

Beyond social reforms and improving the country's infrastructure, Sankara also launched an ambitious public health program. Over two weeks, two million residents, particularly vulnerable children, were vaccinated against deadly diseases such as yellow fever, measles, and meningitis.

In a groundbreaking move, Sankara's government recognized the looming threat of the HIV epidemic, becoming one of the first in Africa to confront the crisis head-on. Child mortality rates plummeted through the establishment of numerous health centers, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's well-being.

The local cotton industry also developed – the government expected its employees to wear uniforms made from home-grown cotton. Agricultural reforms made food production surge, laying the foundation for a self-sufficient nation.

Sankara often said variations of this message:

"A soldier without political education is but a criminal in power."

And in the case of Burkina Faso's military, he put that message into practice. At military bases around the country, he assigned soldiers to cultivate crops, tend livestock, maintain cleanliness in towns and villages, and assist in constructing schools.

The significance of this unconventional approach extended beyond the nation's development. According to journalist Ernest Harsch, who has covered Burkina Faso since 1980, Sankara told him that through farming, the soldiers were reminded of how ordinary people worked and toiled. It fostered a sense of camaraderie, bridging the gap between the military and the people.

Sankara is often associated with Marxist-Leninist ideologies, but he maintained that Burkina Faso did not align itself exclusively with any foreign doctrine, whether from the right or the left. In his office, books by Karl Marx adorned the shelves, an image of Che Guevara was emblazoned on a cloth, and a bust of Lenin rested on his desk.

However, he was also a man of faith. In an interview with Newsweek, he ardently expressed that his government's sole aim was to ensure the people's access to adequate food, clothing, shelter, healthcare, and education.

People often believe that Sankara outright rejected foreign aid. In truth, Burkina Faso relied on extensive financial support, particularly from France and other nations such as the Netherlands, Japan, Cuba, and China.

But Sankara's perspective on aid was a departure from conventional notions of charity. He viewed it as a loan and rejected proposals that might yield short-term benefits but jeopardize the nation's long-term prospects. He tried to forge a future where Burkina Faso could stand independently.

This conviction led him to question the influence of institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, ultimately rejecting their approaches. He believed that yielding too much control to these entities would undermine the sovereignty of Burkina Faso's economy and, by extension, its revolutionary path.

The wheels of progress were turning relentlessly under Thomas Sankara's leadership: he slashed school fees in half, literacy rates soared, new infrastructure stretched across the land with roads, train tracks, and wells, and he introduced a highly ambitious effort to combat desertification by planting ten million trees.

It was a time of remarkable achievements. But there was a downside.

Sankara's critics mobilize

Amid Thomas Sankara's many victories, critics raised concerns about his methods. They pointed out that his approach veered far away from democracy. For example, no other political parties were allowed, and those the government deemed counter-revolutionary could swiftly be dismissed from their posts.

Unions faced opposition as well. In March of 1984, when the country's teachers staged a strike in protest of two colleagues being fired for expressing criticism, the Minister of Education dismissed a thousand more educators.

Officially, the government didn't censor the press and maintained that journalists could criticize their policies. However, in practice, dissenting voices remained unheard. The media landscape became dominated by state-owned outlets when, in June 1984, masked individuals attacked and destroyed the printing office of L'Observateur – the nation's only independent newspaper.

Sankara also established "revolutionary courts", operating outside the regular judicial system and allowing ordinary citizens to witness the trials of corrupt officials and former government members. They sometimes devolved into theatrical spectacles marred by personal vendettas. Defendants lacked lawyers and the chance to appeal, leading to concerns about fairness. While some sentences aimed at deterrence resulted in mild punishments, others delivered harsh prison terms and hefty fines.

Sankara's whirlwind of reforms garnered praise from many quarters but also stirred up a formidable opposition. His approach of immediate implementation, without trial or transition periods, created powerful enemies who resisted the sweeping changes.

The bans on polygamy and female circumcision faced resistance from various groups, not just men, who saw them as encroachments on essential customs. The urban middle class was incensed when the government reduced their salaries and eliminated their bonuses to benefit the rural population.

Moreover, the traditional practice of granting authority to older male village chiefs clashed with the new government's hierarchies. These chiefs, accustomed to wielding power and influence for centuries, were stripped of their ability to extract labor and levy taxes on the populace.

Discontent also seeped into the state apparatus when, starting in August 1985, Sankara initiated an annual program that required ministers and government employees to redeploy to rural areas for various projects.

Sankara aimed to give them firsthand insight into the challenges faced by the people and to emphasize that government officials were not exempt from the responsibilities of ordinary citizens.

Employing his military discipline, he even surprised officials by conducting impromptu inspections of their workspaces. This method drew disapproval from many. Even minor tardiness by as little as five minutes could result in punishments such as evening or weekend shifts.

The order to end an affair with a mistress issued to Captain Gilbert Diendéré triggered outrage among Sankara's close military colleagues. Sankara believed infidelity was incompatible with the revolution's ideals, a stance that some of his male allies found too idealistic and resented.

By early 1987, Sankara found himself increasingly isolated. While he remained popular among most of the population and drew admiration in certain circles abroad for Burkina Faso's rapid progress, the revolutionary fervor had begun to wane. The atmosphere surrounding Sankara had changed, casting a shadow over his once-unified movement.

In the international arena, Thomas Sankara's anti-imperialist rhetoric had strained his relationship with the United States and France. This tension spilled over into conflicts with neighboring Ivory Coast, Mali, and Togo – countries closely aligned with France. Even Libya's Muammar al-Gaddafi, once an ally, had turned his back on Sankara when he refused to allow Libyan-backed rebel troops into the country to prepare a coup in Liberia.

Whispers of a looming revolt within Burkina Faso spread quickly, causing worry among Sankara's closest friends and family. They urged him to strike preemptively, but Sankara chose a different path. He believed shedding blood would only perpetuate an endless cycle of vendettas.

During his speeches in the fall of 1987, Sankara continued his critique of the middle class and political elite, accusing them of exploiting the poor for personal gain. But, he also acknowledged that he might have implemented some changes too hastily, suggesting a "pause" in the revolution to allow society to catch its breath. Whatever he was hoping to achieve, it was already too late.

The assassination of Sankara and its fallout

In the afternoon of October 15, 1987, a vast number of soldiers fell upon the capital, positioning themselves strategically. At the same time, the telecommunications network went silent.

Those closest to Thomas Sankara had pleaded with him to prioritize his safety, but he believed his work couldn't wait. It's difficult to know how conscious Sankara was of his vulnerable position as he sat there in the meeting room with his cabinet.

The details of what unfolded come from Alouna Traoré, the only survivor of the gathering. He has recounted the same version of events since 1987: the eruption of gunfire outside, resembling "heavy rain suddenly coming down on a tin roof"; Sankara, realizing he was the target, calmly leaving the room with his arms raised above his head; how he barely made it out before being fatally shot; the soldiers storming into the room and executing twelve others in cold blood. Traoré was injured in the shooting but survived miraculously.

The attackers had been mobilized by Gilbert Diendéré, the captain Sankara had reprimanded for his extramarital affairs. Blaise Compaoré, Sankara's longtime comrade and close friend, orchestrated the entire takeover. The two had once been so inseparable that people often called them brothers. At one point, Compaoré even lived in Sankara's home, prompting Sankara's wife, Mariam, to joke about them being co-wives.

But now, Compaoré seized control of Burkina Faso. Later that evening, his voice poured out of radios across the country, delivering a speech filled with harsh accusations, painting Sankara as a delusional traitor.

The extent of Sankara's anticipation of Compaoré's betrayal remains debatable. In historian Brian J. Peterson's book, Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa, published in the spring of 2021, various individuals with intimate knowledge of the events provide insights.

Some believe that Sankara had already sensed the inevitability of his demise and did not want to risk dragging Burkina Faso into a potential civil war by attempting to defuse the looming threat. Others argue that Sankara's trusting nature proved to be his downfall.

Under the cover of night, the lifeless bodies were loaded onto a truck, driven to a burial site in one of Ouagadougou's impoverished neighborhoods, and hastily dumped into freshly dug graves. Sankara was only thirty-seven years old, and the revolution had recently celebrated its fourth anniversary.

The news of Sankara's assassination sent shockwaves throughout the nation. While Burkina Faso had grown accustomed to coups, this was the first time a president had been assassinated.

Compaoré vehemently denied any involvement, concocting a narrative in which his troops had discovered a plot orchestrated by Sankara. According to Compaoré, the soldiers attempted to apprehend Sankara, but he allegedly responded with gunfire, forcing them to shoot him in self-defense. All but Compaoré's staunchest allies rejected his version of events immediately.

The question of France's involvement in Sankara's assassination has ignited passionate debates among historians, political commentators, and ordinary people in Burkina Faso and beyond. Some view it as a meticulously planned French operation. In contrast, others see it as the culmination of an internal power struggle.

Brian J. Peterson offers a nuanced perspective, suggesting that while France may not have directly participated militarily, it played a role in creating the conditions for the coup. This included exerting financial pressure, smearing him in the media, and fostering dissent within Sankara's party.

Numerous efforts have been made to pressure France into releasing classified documents that could shed light on its potential responsibility, so far without success.

During his life and even more after his murder, Sankara transcended his role as a national figure and became a global symbol of pan-Africanism, self-sufficiency, anti-imperialism, and anti-corruption. However, within Burkina Faso, he faced vilification. Compaoré attempted to portray himself as the true revolutionary who genuinely cared about the people.

On the international stage, however, Compaoré sought to present himself as a pragmatic and level-headed leader, distancing himself from Sankara's radical ideas. He eagerly embraced collaborations with Western powers and swiftly signed agreements with institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. As a result, major Western countries welcomed him as a refreshing and cooperative presence.

Back in Burkina Faso, Compaoré dismantled the revolution's achievements. The new regime, lacking popular support, relied on the upper middle class, traditional village chiefs, and members of the pre-revolutionary political elite – groups that had historically held power in the country and with whom Sankara had alienated himself. Corruption once again infiltrated everyday life.

Blaise Compaoré held the reins of power in Burkina Faso for twenty-seven years until 2014, when his attempts to change the constitution and extend his term ignited intense protests.

During these demonstrations, activists fervently chanted Sankara's name, his face adorned placards and t-shirts, and protesters quoted his words in speeches. Eventually, Compaoré fled the country, seeking refuge in the Ivory Coast. In 2015, a new presidential election took place, resulting in the victory of former Prime Minister Roch Marc Christian Kaboré.

Sankara's widow, family, and supporters had long fought to bring the guilty to justice. With the departure of Compaoré, their opportunity arrived. In 2015, Sankara's body was exhumed, and an autopsy revealed that he had suffered more than twelve gunshot wounds.

Then, in April 2021, a military court in Burkina Faso finally brought charges against Blaise Compaoré and 13 others, accusing them of complicity in the murder. The long-awaited trial commenced in October, albeit without Compaoré, who defiantly boycotted the proceedings, asserting his immunity as a former head of state. Having acquired Ivorian citizenship during his time in exile, his release now hinged on the permission of the Ivorian government.

But then, a familiar pattern occurred, rattling the nation once more.

A new round of military takeovers

It's Sunday, January 23, 2022. Mobile networks abruptly went silent, and gunfire reverberated from various military barracks nationwide. As evening neared, shots rang out near the presidential palace.

The next day, soldiers took over the state radio and television station. Hours later, they broadcast a speech to the nation.

In the broadcast, fourteen soldiers emerged, clad in desert camouflage. Some sported red and blue berets, while others donned helmets and face masks. Automatic weapons rested in the hands of several.

They identified themselves as the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration, declaring that they had ousted the president due to his failure to stop the deteriorating security situation.

Since 2015, jihadist groups in northern Burkina Faso have unleashed deadly attacks, resulting in thousands dead and displacing nearly two million people. Similar groups have emerged in Mali, Chad, and across the Sahel region, taking advantage of the influx of weapons following Gaddafi's fall in Libya in 2011.

During their speech, the soldiers announced the dissolution of parliament and the government. They closed the borders and enforced new curfews.

A week later, the soldiers reintroduced the constitution and appointed Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba as the new president. In March, the junta declared its intention to hold elections after a three-year transitional period.

The trial against Compaoré pressed forward amidst the precarious state of affairs in the country. The verdict was delivered on April 3, 2022 – a life sentence for Compaoré and two cronies. Eight of the remaining eleven defendants received prison terms ranging from three to twenty years, while the remaining three were acquitted.

Curiously, despite the gravity of his sentence, the new president permitted Compaoré to return to Burkina Faso for a conference attended by several former leaders of the country. Lawyers representing the Sankara family called for his arrest, but their pleas were brushed aside.

In a letter read aloud by a spokesperson, Compaoré offered an apology of sorts:

"I ask the Burkinabe people for forgiveness for all the acts I may have committed during my tenure, and especially the family of my brother and friend Thomas Sankara. I take responsibility for, and regret from the bottom of my heart, all the suffering and tragedies experienced by all victims during my terms as leader of the country and ask their families to grant me their forgiveness."

The response to his apology was a mixed bag. Some factions deemed it insufficient, contending that justice remained elusive as long as he walked free. However, this time, the battle against the jihadists took center stage, overshadowing other concerns. Compaoré's freedom was seemingly secured, as the conference was meant to symbolize national unity in the face of rebel insurgency.

But the spiral of violent military takeovers continued. In September 2022, another coup took place in Burkina Faso, which brought a relatively unknown leader to power, the 34-year-old Ibrahim Traoré, with a claimed past in a counterterrorist unit.

The enigmatic and reclusive Ibrahim Traoré has left an outsized mark on Burkina Faso during his brief rule. In January 2023, his leadership delivered a seismic announcement: military cooperation with France would end, and French forces were given four weeks to leave the country. By February, the withdrawal was complete. In France's place, Burkina Faso began forging closer ties with Russia and Turkey.

Yet, at the time of writing, the country's security crisis shows no signs of easing. Violence is escalating, and the humanitarian disaster deepens. Thousands have been killed or displaced, and the insecurity has forced the closure of thousands of schools, leaving more than a million children without access to education.

The junta, which once promised a return to democracy by mid‑2024, has since abandoned that timeline. Citing the deteriorating security situation, leaders declared that no elections would be held until stability could be ensured.

In May 2024, they extended their transitional rule by five more years, pushing any potential return to civilian governance far into the future.

Then, in the summer of 2025, they dissolved the independent electoral commission, transferring oversight of elections to the interior ministry, a move widely viewed as further consolidating power in military hands.

Can Burkina Faso's insurgency be contained? And if so, will the military honor its promise to relinquish power? Or will it succumb to the familiar temptations of juntas throughout history, clinging to authority and suppressing democratic aspirations?

It's still an open and deeply uncertain question.

The legacy of Sankara

Is there such a thing as a good-hearted dictator? Some would say that Thomas Sankara is an example of one. Or, that he's as close as you're gonna get. Others would say that his uncompromising nature showed signs of an authoritarian side, which had already begun to, and in time would've continued to, lead to an abuse of power.

Lord Acton, an English historian, is known for a letter he sent to a bishop in 1887. In the letter, he wrote:

"Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely."

It's of course impossible to say what would've happened had Sankara not been assassinated, or in which direction he would have developed.

However, one thing is evident: During the 1980s, when many other African leaders seemed to engage in a contest of who could be most corrupt, selfishly enriching themselves at the expense of their nations, Sankara offered an alternative path.

Instead of succumbing to the temptation of personal gain, he instilled national pride, self-confidence, and hope for self-sufficiency.

Further reading:

Books:

Women's Liberation and the African Freedom Struggle by Thomas Sankara (2007)

Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary by Ernest Harsch (2014)

A Certain Amount of Madness: The Life, Politics and Legacies of Thomas Sankara by Amber Murrey, editor (2018)

Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa by Brian J. Peterson (2021)

Articles:

"13 killed in coup in Upper Volta" in New York Times (August 6, 1983)

"Africa's' upright people': Still has no clear answers" by Alan Cowell in The New York Times (January 9, 1985)

"Young Voice in Africa: Sports and Clean Living" by James Brooke in The New York Times (August 23, 1987)

"A friendship dies in a bloody coup" by James Brooke, The New York Times (October 26, 1987)

"Sankara: daring to invent Africa's future" by Sean Jacobs in The Guardian (October 15, 2008)

"Burkina Faso's revolutionary hero Thomas Sankara to be exhumed" by David Smith in The Guardian (March 6, 2015)

"Thomas Sankara: Body of Africa's Che Guevara riddled with bullets, autopsy reveals three decades after death" by Ludovica Iaccino in International Business Times (October 14, 2015)

"Burkina Faso wants France to release Sankara archives'" by BBC (October 13, 2016)

"Thomas Sankara and the Revolutionary Birth of Burkina Faso" by Mamadou Diallo in Viewpoint Magazine (February 1, 2018)

"Thomas Sankara had two faces – Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo" by Aïssatou Diallo in The Africa Report (March 4, 2020)

"Burkinabe ex-President Compaoré charged in Thomas Sankara murder" by Henry Wilkins in Al Jazeera (April 13, 2021)

”Burkina Fasos störtade president åtalas för mordet på sin företrädare” by Erik Esbjörnsson in Dagens Nyheter (April 14, 2021)

Scholarly articles:

"Ideology and Praxis in Thomas Sankara's Populist Revolution of August 4, 1983 in Burkina Faso" by Guy Martin in Issue: A Journal of Opinion (vol. 15, 1987)

"Sankara and the Burkinabe Revolution: Charisma and Power, Local and External Dimensions" by Elliott P. Skinner in The Journal of Modern African Studies (vol. 26, nr 3, 1988)