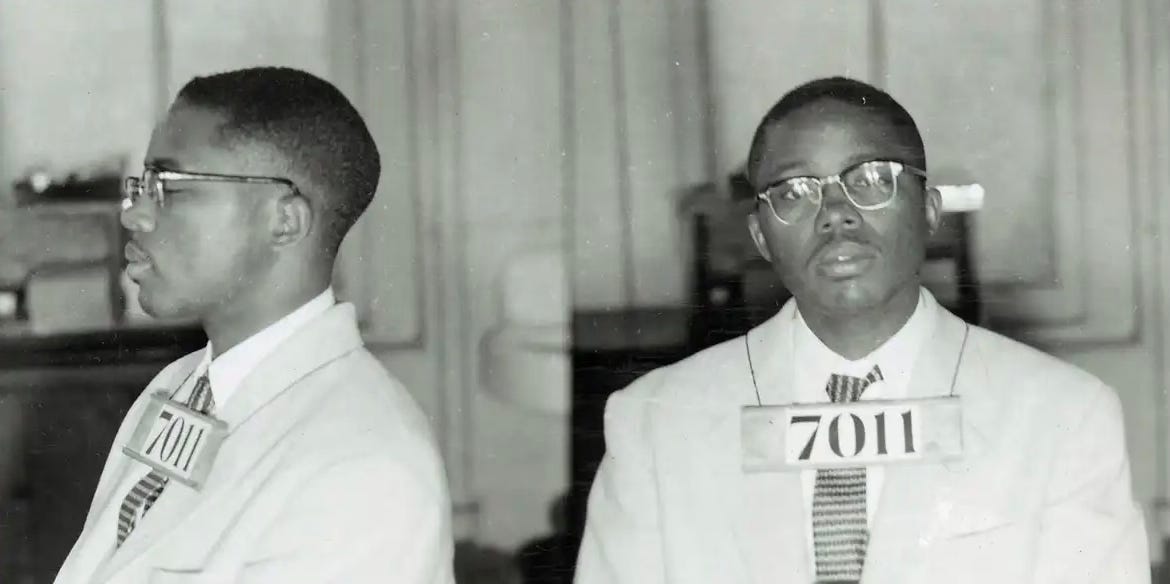

Claudette Colvin (1939-2026)

Not the face of the Montgomery bus boycott – but a force behind dismantling segregation

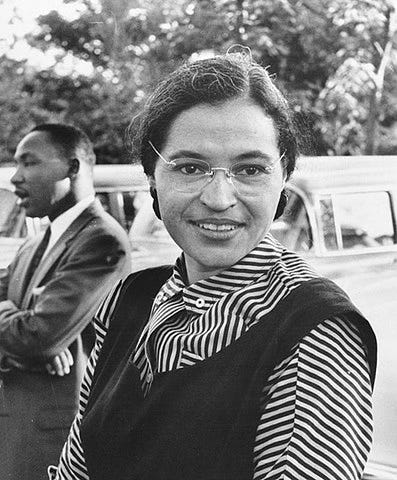

Most people know the story of Rosa Parks, who in December 1955 refused to surrender her seat to a white man on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her quiet act of defiance ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott, one of the defining actions of the modern American civil rights movement.

But nine months earlier, on March 2, 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin took a similar stand. Born in 1939, Colvin grew up poor and attended one of Montgomery’s segregated Black schools.

One afternoon, Colvin and three classmates boarded a city bus home. The first ten rows were reserved for white passengers, even though most riders were Black. The girls sat in the white section anyway. As the bus filled and a white woman was left standing, the driver ordered the young Black girls to give up their seats. Colvin’s friends complied. Colvin did not. Politically aware and unflinching, she stayed where she was.

Police arrested her for violating segregation laws, but she refused to accept the charge. Instead, she insisted on her constitutional right to sit wherever she chose. Colvin was not the first person to challenge bus segregation in this way, but she stood out for her determination to push the matter further, despite her age. She reached out to Fred Gray, one of only two Black attorneys practicing in Montgomery at the time.

The 1950s were a period when Black Americans were routinely subjected to violence: from the police, from the Ku Klux Klan, and from ordinary white citizens. For many activists, minimizing risk was therefore a matter of survival.

It was also before Malcolm X had emerged as a nationally prominent political figure, and long before the Black Panthers were founded. Within the civil rights movement, the prevailing belief was that Black Americans stood the best chance of achieving legal progress if they appeared respectable, articulate, and committed to nonviolence.

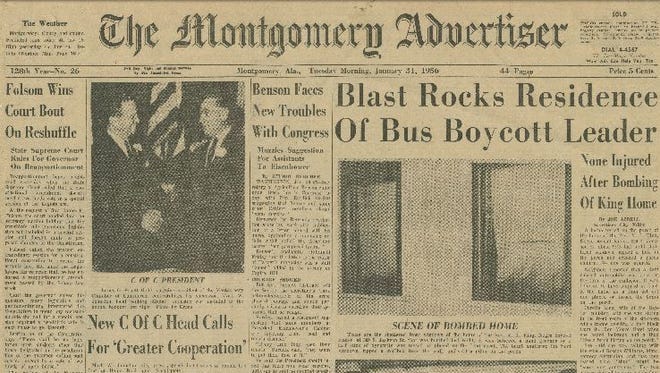

Activists held fast to this belief even as reality repeatedly contradicted it: police wielded batons, unleashed water cannons and dogs, while segregationists answered with ropes, torches, and bombs.

For these reasons, leaders of the local civil rights movement chose to remain silent about Colvin’s case for a long time. She was young, unemployed, and from a working-class background. She also soon became pregnant by a man she was not married to. Movement leaders feared that white media would easily discredit her, portraying her as morally suspect and undermining the broader struggle.

Instead, Rosa Parks – 42 years old and a respected member of the NAACP – was positioned as the public face of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Colorism likely played a role as well. Colvin was dark-skinned, Parks was light-skinned, and under prevailing racial assumptions, Parks was seen as less threatening and more sympathetic.

Parks was indispensable in mobilizing mass support for the movement. But in legal terms, Colvin’s impact was even greater. She was one of four plaintiffs – alongside Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith – in the landmark Browder v. Gayle case. In 1956, a federal court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional, a decision later upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Due to the upheaval, Colvin afterwards moved to New York, where she worked for most of her adult life as a nursing assistant.

Today, news broke that Claudette Colvin has died, aged 86. She was one of the civil rights movement’s quieter giants – a reminder that behind its most celebrated icons stand countless others whose contributions were decisive, whose courage mattered, and whose names history too often leaves behind.

An equally vital lesson for today’s resistance movements.