Assata Shakur (1947-2025)

Freedom in Exile

JoAnne Deborah Byron was born in New York in 1947 but spent parts of her childhood in the Jim Crow South of segregated North Carolina. As a young woman, she enrolled at a community college in Manhattan, where she was quickly drawn into activist circles. There, she was introduced to socialist ideas and global independence struggles that connected Harlem to global liberation movements.

Byron found the argument persuasive that racism could not be defeated without also dismantling capitalism. Yet she kept her distance from the socialist groups she encountered – she bristled at the arrogance of their mostly older white members, who insisted they alone knew the path to Black freedom.

After finishing community college, Byron entered the City College of New York, where she met fellow student Louis Chesimard, whose revolutionary zeal matched her own.

They married in 1967, but their union was short-lived. JoAnne Chesimard, as she now called herself, spent nearly every waking hour in class, at meetings, or in protests. Her husband, who had imagined a traditional housewife, found himself with a partner whose only kitchen specialty was spaghetti. They divorced after just over a year.

Free from marriage, JoAnne Chesimard moved west to Oakland, California – the birthplace of the Black Panther Party and a hotbed of radical politics. In Oakland, she connected with the Red Guard Party, a group of young Chinese Americans fighting abysmal conditions in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and the Brown Berets, Chicano activists who resisted the Vietnam War, battled police brutality, and stood up for farmworkers’ rights.

Connecting liberation movements across racial boundaries, and even finding common ground with independence movements in Africa, South America, and Asia, was a key agenda item for the American civil rights movement in the late 1960s. For Chesimard, this bridging of struggles felt natural.

From the Black Panthers to the Black Liberation Army

Still, the group that most captured her imagination was the Black Panthers. Their radical politics, bold rhetoric, and striking visual style made a deep impression. She visited their headquarters, got to know members, and did odd jobs, though she initially stopped short of joining.

That changed in the early 1970s, when the government’s efforts to prosecute Black Panther icon Angela Davis made headlines. Chesimard resolved that once back in New York, she would join the Harlem branch of the Panthers. Around this time, she also chose a new name: Assata Shakur. Identifying as an African woman, she felt the name expressed her true self.

As a Panther, her first role was in the group’s health department, where she scheduled dental visits, taught first aid, and raised awareness about sickle cell anemia.

She later joined the famous breakfast program that fed thousands of poor schoolchildren across U.S. cities. Every morning, Panthers gathered in churches and community centers to prepare meals, ensuring that children could arrive at school nourished and ready to learn.

Over time, however, Shakur became increasingly dissatisfied with the Black Panthers’ leadership and direction. She felt that there was no room for constructive criticism and that the organization was characterized by a lack of routines, problems that were exacerbated by the paranoia that had taken root among members as a result of the FBI’s infiltration and divisive tactics. The FBI viewed the Black Panthers as a domestic terrorist organization and, as part of the illegal and then-unknown COINTELPRO program, sought to disrupt and sabotage the group.

On top of that, Shakur was angered by the male chauvinism that kept women in subordinate roles.

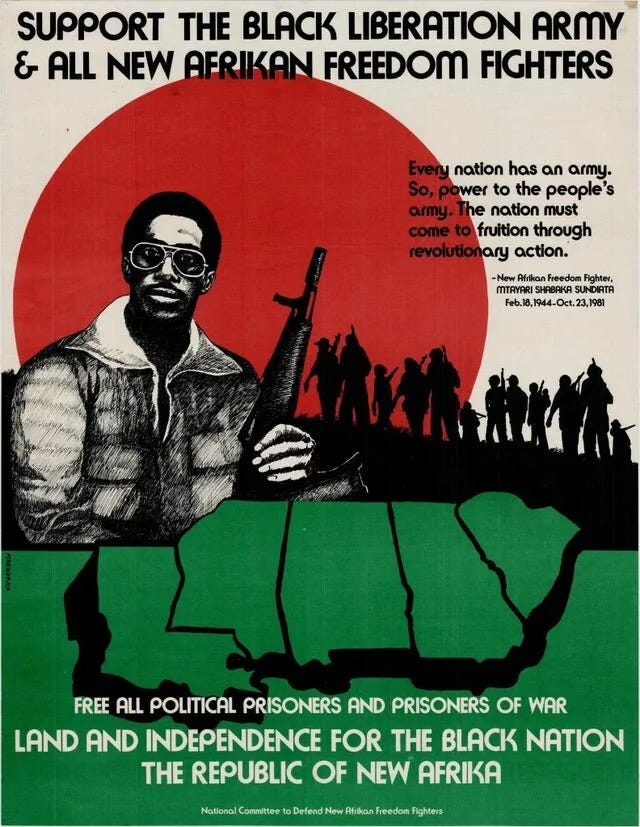

In 1971, she broke away and joined the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Its exact size and significance remain debated: police called it an armed urban guerrilla force bent on assassinating officers. They even labeled it a terrorist sect funded through bank robberies. Authorities cast Shakur as the movement’s “soul,” tying her to murders and armed robberies.

Shakur herself rejected that portrayal. She described the BLA not as a formal group but as a loose network of Black revolutionaries committed to self-defense and liberation. To her, the accusations were part of a smear campaign designed to discredit a popular movement born out of oppression.

It’s still not fully established how the Black Liberation Army started. The movement probably gained new members as a result of the FBI’s opposition to the Black Panthers. In its 1975 manifesto, following the BLA’s attempt to centralize its organization, the group stated that anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism, anti-racism, and anti-sexism were the movement’s watchwords.

New Jersey Turnpike Shootout

On the night of May 2, 1973, Assata Shakur was driving along the New Jersey Turnpike with two other BLA members, Zayd Shakur and Sundiata Acoli, when state troopers pulled them over for speeding. What happened next is disputed.

What’s clear is that a shootout erupted, leaving Zayd Shakur and one officer dead, Assata Shakur and the other officer wounded. Assata fled in the chaos but was caught within half an hour. Acoli evaded capture for 36 hours before being arrested in a massive manhunt.

Gravely injured, Assata was taken to a hospital where she insisted she had not fired a weapon. From her hospital bed, she was interrogated and, according to her testimony, beaten whenever staff left the room – claims the police denied. She was later transferred into custody to await trial.

Determined to silence one of the Black Liberation Army’s most visible figures, the state hit Assata Shakur with a barrage of charges: bank robberies, kidnappings, even murder. Over the next few years, seven cases went to trial. In six, the prosecutions collapsed through acquittals, lack of evidence, or sheer technicalities.

The seventh trial was different. Although fellow BLA member Sundiata Acoli had already been convicted of killing the state trooper in the 1973 New Jersey shootout, prosecutors argued that Shakur’s very presence made her an accessory to murder, whether or not she had fired a bullet. In February 1977, a nine-week, media-saturated trial began.

Testimony clashed. Shakur insisted she had never touched a weapon, that she had her arms raised when police shot her. A surviving officer swore she had fired first. Shakur’s lawyers called a neurologist and a pathologist, both of whom testified that her injuries indicated that she had had her hands in the air when she was shot.

Yet the odds were stacked: all fifteen jurors were white, and five had close ties to state troopers. On March 25, 1977, the verdict came down: life in prison.'

Serving Time

After the verdict, she was transferred to Rikers Island in New York. By then, Shakur was pregnant. That September, under heavy guard at a Queens hospital, she gave birth to her daughter Kakuya, fathered by Kamau Sadiki (formerly Fred Hilton), himself a co-defendant in another case. Days later, she was sent back to Rikers Island, where she would endure nearly two years in solitary confinement while her mother raised the baby.

Prison transfers followed. In 1978, she was moved to West Virginia’s Alderson Federal Prison Camp, confined in a maximum-security unit she said was shared with members of the “Aryan Sisterhood.” Two months later, she was relocated again, this time to the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in New Jersey.

The Escape

Her comrades in the Black Liberation Army had not forgotten her. To fund a rescue, BLA members robbed a New Jersey department store. On November 2, 1979, three of them entered the prison with fake IDs, smuggled guns inside, and took two guards hostage. Within minutes, they spirited Shakur out, hijacked a police van, and vanished. They drove the bus to a parking lot where they abandoned the vehicle and the two prison guards, before jumping into two getaway cars.

The FBI unleashed a sweeping manhunt across New York and New Jersey. But the search met resistance: communities often greeted wanted posters with signs declaring, “Assata Shakur is welcome here.”

For years, she lived underground. Then, in 1984, she resurfaced in Cuba, granted political asylum on the grounds that her trial had been unjust. Her presence became public in 1987, when she gave an interview to Newsday and published her influential memoir, Assata: An Autobiography. Her daughter soon joined her on the island.

From exile, Assata Shakur became one of the most influential yet controversial figures in the Black liberation movement. For many, she was the embodiment of radical resistance to racism, police brutality, and state oppression. She was considered the godmother of legendary rapper 2Pac and has long enjoyed iconic status in hip-hop.

But for others, who buy the U.S. authorities’ version of events in the turnpike shooting, she was little more than a police killer.

Despite escaping the law, the authorities never let up. In 2013, she became the first woman to appear on the FBI’s “Most Wanted Terrorists” list. Both the FBI and New Jersey offered $1 million each for information leading to her arrest.

Several attempts were made to extradite her, including by President Donald Trump in 2017. Trump used her extradition as one of the demands for the United States to continue the thawing process that was started under Barack Obama. But Cuba consistently refused.

On September 26, Cuban authorities announced that Assata Shakur had died the previous day, from health problems and advanced age. Her passing is sure to reignite debate over her life and legacy.

With her many decades on the island, Shakur became one of the biggest names to survive the violent repression of Black freedom movements by the American state.

Cuba had been her refuge. It was where she found safety, where she raised her daughter, where she wrote her story. And in the end, it was where she died.

Exiled, but free.

Further reading:

Books:

Assata: An Autobiography by Assata Shakur (1987)

Liberation, Imagination and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Black Panthers and Their Legacy by Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficas (editors.) (2001)

Articles:

”Evidence of ’Liberation Army’ Said to Rise” by Michael T. Icaufman for New York Times (February 17, 1972)

”Panther, Trooper Slain in Shoot-out” by Joseph F. Sullivan for New York Times (May 3, 1973)

”Group Claims Role in Florida Killings” for New York Times (June 24, 1974)

”Jury in Chesimard Murder Trial Listens to State Police Radio Tapes” by Walter H. Waggoner for New York Times (February 17, 1977)

”Joanne Chesimard Convicted in Killing Of Jersey Trooper” by Walter H. Waggoner for New York Times (March 26, 1977)

”Miss Chesimard Flees Jersey Prison, Helped By 3 Armed ’Visitors’” by Robert Hanley for New York Times (November 3, 1979)

”On the run with Assata Shakur” by Ron Howell for Newsday (October 11, 1987)

”Fugitive Murderer Reported in Cuba” by John. T McQuiston for New York Times (October 12, 1987)

”Assata Shakur was convicted of murder. Is she a terrorist?” by Krissah Thompson for Washington Post (May 8, 2013)

”Trump to Cuba: Return woman convicted in trooper’s murder” by Associated Press (June 16, 2017)

”Cuba Won’t Negotiate Trump’s New Policy” by Aria Bendix for The Atlantic (June 19, 2017)

”Assata Shakur, convicted of killing a police officer, still wanted by FBI 40 years after fleeing to Cuba” by Christina Carrega for ABC News (May 16, 2019)

Other:

Message to the Black Movement: A Political Statement from the Black Underground by The Black Liberation Army Coordinating Committee (1975)

”The Black Liberation Army: Understanding – Monitoring – Controlling” by The Maryland State Police Criminal Intelligence Division (1991)